Appendices: Public Interest Investigation into RCMP Member Conduct Related to the 2010 G8 and G20 Summits

Appendix A: Initial Complaint Letter from the Canadian Civil Liberties Association

Mr. lan McPhail, Commission Chair

Commission for Public Complaints

Against the RCMP

7337 137 Street, Suite #102

Surrey, BC V3W 1A4

Dear Mr. McPhail:

On behalf of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, I am writing to lodge a formal complaint under Section 45.35 of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act in relation to the RCMP's conduct during the G8 and G20 Summits held in Toronto and Huntsville, Ontario. As you are undoubtedly aware, police activity during these Summits resulted in significant violations of Canadians' constitutional liberties. The RCMP was the lead police agency for both the G8 and G20 Summits and played a significant role in the planning and implementation of Summit security. Until the RCMP is held accountable for its actions during the G8 and G20 Summits, lingering questions will remain that threaten to further erode the public's already fragile confidence in the service. The CCLA had 50 independent human rights monitors at the G20 Summit. Based on their observations, we published a preliminary report on G20 policing on June 29th, a copy of which is enclosed for your review. Our monitors observed many troubling incidents during the G20 Summit, some of which are further described below.

While the CCLA considers a federal public inquiry to be the best mechanism to address this situation, we also believe that the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP (CPC) has a vital role to play in ensuring accountability for the RCMP's actions during the G8 and G20 Summits. Accordingly, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association requests that the Commission provide for an investigation of the extent to which the RCMP was involved in the following matters and the extent to which its members' conduct breached constitutional, international and professional standards:

The RCMP's Role In G8 And G20 Security Planning

As a key member in the Integrated Security Unit, the RCMP was primarily responsible for securing the Summit site and surrounding areas and ensuring the safety and security of Internationally Protected Persons. These responsibilities encompassed a significant decision-making role with respect to the location of the massive fence surrounding the G20 Summit site and the measures that were taken to secure that fence and the area within it. Cordoning off large areas of the city impairs vital democratic rights and freedoms. Section 7 of the Charter guarantees individual liberty, including freedom of movement. Sections 2(b), (c) and (d) of the Charter guarantee freedom of expression, freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of association. The Charter requires that any infringement of individual rights and liberties-including restrictions due to the establishment of security perimeters-impair rights as little as possible. The establishment of security perimeters was addressed at the APEC Inquiry. In the Commission's Interim Report, Mr. Hughes noted that a fence line designed to significantly distance protesters and maintain a "retreat-like atmosphere" could well violate the Charter. To the extent that the conduct of the RCMP contributed to such conditions during the G20, the service and its members must be held accountable.

RCMP Infiltration And Surveillance Before And During The Summits

According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, the RCMP was allocated $507-million for summit security and deployed nearly 5000 officers. An untold number of CSIS agents were also deployed. Both agencies participated in infiltration/surveillance operations in the months preceding the Summits to gather intelligence on protest groups.

The use of such tactics, particularly in relation to non-violent political groups, raises troubling concerns for civil liberties. As such, it is imperative that the CPC review the RCMP's surveillance activities prior to and during the Summits to determine whether they were in accordance with Canadians' rights to freedom of expression and association. Such a review should inquire into how many groups were subject to infiltration/surveillance and whether those groups had an actual connection to criminal or injurious conduct. Particular attention should be given to the RCMP's role in the surveillance of student groups from Quebec and the extent to which such groups may have been unwarrantedly targeted for heightened scrutiny.

Many protesters have complained to the CCLA about being approached by police officers prior to the Summit, voicing concerns that police may have overstepped appropriate boundaries in pursuing pre-Summit intelligence at individuals' homes or places or work. As such, the CPC's investigation should inquire into whether there were any limits on the scope of activities that RCMP informants could engage in while working undercover in protest groups. Specifically, the CPC should probe whether there were limits imposed on the scope of intelligence gathering strategies, the encouragement of particular demonstration tactics, or the organization of particular demonstrations leading up to the Summits.

Excessive Force, Mass Detentions And Mass Arrests

By the end of the G20 Summit, 1105 people had been arrested on the streets of Toronto and a far greater number had been detained. Peaceful protests had been aggressively dispersed and constitutional rights had been curtailed. In many case, police responses were completely disproportionate to any potential security threats. Indeed, excessive force was used against crowds of peaceful protestors and passersby. To our knowledge, the RCMP was not the lead police service involved in these actions beyond the perimeter of the fence; however, the RCMP was responsible for developing much of the G20 policing strategy and it must be held accountable for its involvement in these actions. Below we draw your attention to some of the many examples of excessive policing practices during the G20 Summit. We respectfully ask that you inquire into whether the RCMP participated in, was consulted as part of, or communicated intelligence or information that justified these actions:

1. The Dispersal of Peaceful Protesters at Queens Park on June 26th, 2010

Prior to the G20 Summit, the Integrated Security Unit announced that Queen's Park was a "designated protest zone". Protestors were strongly encouraged to congregate at Queen's Park and use this site for peaceful assemblies and demonstrations. However, by 6pm on June 26th, over one hundred police in riot gear had advanced upon the crowd of peaceful protestors gathered at Queen's Park and ordered them to leave. Police beat their batons against their shields, proceeding in an 'advance and wait' pattern upon protestors, forcing them from the designated protest space at Queen's Park. Police on foot and/or mounted on horses advanced blocking the crowds from moving south on University, and pushing the crowds north. A large presence of unmarked police cars and minivans were lined up south of the perimeter.

Protestors remarked "why are you doing this" and "this is a peaceful protest". Witnesses observed one individual being pushed to the curb, face on the pavement, while an officer kept a knee on the person's head. Other individuals were pulled from the crowd by police, dragged behind police lines, pushed to the ground, had their hands restrained, and were arrested. One of the CCLA's monitors observed a horse running over a protestor. Observers also witnessed police firing guns with what appeared to be blanks or rubber bullets.

At approximately 7:50pm, police continued to push the crowds north, and stated "Move back or you will be arrested. The police are advancing"; "back up, back up"; or "move, move. Now. Move it", and "Please clear the park". Protestors were heard asking "This is the designated protest area, why do we have to leave the park?". The police continued to advance upon the crowd, stopping, and then resuming their advance. One officer in the line had his gun raised and pointed at the crowd. The crowd was eventually pushed out of the park in this manner, with three lines of officers forcing the crowd's dispersal. Police were seen holding their shields up, wielding batons, and pushing protestors back.

2. Detentions and Mass Arrests at the Esplanade

A large crowd of protestors gathered in front of the Novotel on the Esplanade, on the evening of June 26th, 2010. Most of the crowd was sitting, following chants by some of the protestors to "sit down" and "peaceful protest". The police engaged some members of the crowd to ask questions, and observers noted the conversations to pass peaceably and uneventfully. Suddenly, pairs of police began to approach the crowd, grab seated demonstrators, and remove them with their arms behind their backs. It became clear that the protestors were not allowed to leave the area, which was blocked by buildings or by police dressed in riot gear. A member of the crowd announced to the police "we are not under arrest; you do not have the right to contain us here with no way out".

Over a twenty-minute period police began to move periodically forward, confining the crowd to a smaller and smaller space. No announcement was made to the crowd, until the police called upon the crowd to be quiet, and announced that everybody was under arrest. Over the next three hours, individuals trapped on the Esplanade in police lines were arrested-their hands restrained by metal cuffs and then, after processing which in many cases took hours, by plastic zip ties-and removed from the Esplanade by bus or van to the Eastern Avenue Detention Centre. Two CCLA monitors were arrested despite their identification.

3. Prolonged Detention and Mass Arrest at Queen and Spadina

On the evening of June 27th, 2010, individuals who were protesting peacefully, journalists, and passersby at Queen St. W. and Spadina Avenue were contained by police, hemmed in, and not allowed to leave. During this time, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association received calls from members of the public who reported that they had not been protesting, wanted to go home, but were boxed in on all sides by the police and not permitted to leave. These individuals expressed fear and frustration, and were at a loss as to how to get out of the situation.

The police charged on peaceful protestors, preventing a peaceful demonstration. Mass arrests occurred and individuals were transported to the Eastern Avenue Detention Centre. Others were detained on site, in the rain, or kept for hours in vans, and denied requests to use washroom facilities. Some individuals report being taken to a police station in Scarborough and then released hours later into the night. Some individuals reported that their property was damaged as a result of long-term exposure to the rain. Three of the CCLA's legal monitors were arrested.

4. Arrests and Police Conduct Outside the Eastern Ave.Detention Centre

Approximately 100 protestors gathered the morning of June 27th, 2010 at the Eastern Avenue Detention Centre, in a "celebratory" atmosphere. There was cheering as individuals were released from inside the Detention Centre; a demonstrator played guitar. Protestors also chanted peacefully, including the chant "peaceful protest". Initially, there were only minimal police-about 5-10-between the crowd and the Detention Centre.

Then more police arrived in unmarked vans. Several (approx. 5) plain-clothed police jumped out of one of the vans and ran into the crowds, where they proceeded to grab at least three people and roughly remove them from the crowds. One of the people was thrown into the back of the van, and the van sped off extremely quickly. Two other people were pulled out of the crowd, one man and one woman. They were treated roughly, and forced to lie on the ground with a police officer's knee in the woman's back, and a police officer's boot on the man's head. These people were held down against the pavement.

Riot police began to appear in dozens. The riot police lined up in front of the detention centre. Some kind of weapon was fired upon the crowd emitting white smoke.

Protestors were ordered to leave. Protestors and monitors were very confused as to why the police used excessive force by firing indiscriminately upon the crowd, and dispersing the legal and peaceful demonstration.

5. Mass arrests at the Graduate residence

Police raided the University of Toronto's Graduate Students' Union building early in the morning on Sunday June 27th, arresting a large number of individuals who had been billeted in the building's gymnasium over the weekend. The raid was reportedly executed on the basis of "information" rather than as a result of a disturbance at the building. A CCLA monitor present on the scene counted 97 people being arrested, many of whom were in their pyjamas. One RCMP officer was observed at the site of the arrests, which resulted in the detention of a large group of people from Quebec.

In the CCLA's view, these incidents constitute a failure to protect and facilitate peaceful assembly and the exercise of freedom of expression through protest. They also constitute illegal containment, detention and mass arrest. The CCLA calls upon the CPC to investigate and examine the role that RCMP officers and staff played in decisions involving the use of force, arrests and detentions during the G8 and G20, both in the context of the above mentioned incidents and beyond.

Unlawful Conditions Of Detention

Many persons arrested during the G20 Summit were subsequently sent to a temporary detention centre which police had established on Eastern Avenue in Toronto's east end. Reports about the conditions at this detention centre are highly troubling, indicating a widespread lack of respect for both detainees and their Charter rights. Many persons detained at the Eastern Avenue detention centre were kept with their hands bound for the duration of their detention. Although some detainees complained that their hands were bound too tightly, the hand ties were not adjusted in a timely manner. Inappropriate comments, including sexually inappropriate comments, were apparently made by police to detainees and several individuals complained of being taunted by police. Some detainees were not given adequate water - over an eighteen hour period one detainee tells us only two Dixie-sized cups of water were provided and one of those cups contained brown, undrinkable water. At least one detainee was diabetic and requested insulin for hours before being attended to, and then apparently was administered the wrong type of insulin for his condition.

Chaotic conditions prevented access to lawyers and family members in an appropriate timeframe. Indeed, many persons held at the Eastern Avenue detention centre were not permitted to phone anyone during their detentions, including legal counsel. There was a failure to provide adequate food, water, proper medical attention, and bathroom conditions/facilities. The conditions did not comply with basic standards of detention. For example, a special needs person was deprived of his wheelchair, and released over ten hours after detention into the street without his wheelchair.

The CCLA believes that the detention conditions at the Eastern Avenue detention centre contravened due process rights guaranteed by the Charter, and Canadian and international standards of detention given the lack of access to counsel, lack of food, inadequate availability of water, and inadequate medical attention. It is unclear to what extent the RCMP was involved in running the Eastern Ave. detention centre; however, in the CCLA's view, the RCMP's primary role in organizing and planning security for the G20 Summit imposes upon it an obligation to ensure the presence of adequate detention facilities.

The CCLA believes that the above-mentioned police action violated constitutional rights guaranteed in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms including:

- The right to peaceful assembly and association;

- The right to freedom of expression;

- The right to be free of unreasonable search and seizure;

- The right to be free from arbitrary arrest and detention;

- The right to liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice;

- The right to due process including the right to legal counsel upon arrest;

- The right to be free from discrimination, including on the basis of age, sex, and national origin.

The CCLA is also concerned that police action during the G8 and G20 Summits violated international standards of policing including:

- The duty of police to protect and facilitate peaceful protesting;

- The duty of police to ensure that any arrests made during an assembly are based upon a reasonable suspicion that an individual is about to commit a crime or offence; arrests made during an assembly must be limited to persons engaging in conduct that is creating a 'clear and present danger of imminent violence';

- The duty of police to ensure that adequate food, water and hygiene-including gender appropriate washroom facilities-are provided for detainees and that adequate facilities are provided to ensure access to a lawyers and family.

At this point, a thorough investigation of the RCMP's conduct during the G8 and G20 Summits is required to clear the air and ensure that public confidence in the RCMP is not further eroded. This investigation must examine the policy and conduct of RCMP officers prior to and during the G8 and G20 Summits, with a focus on the above-mentioned issues and incidents. Accordingly, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association calls upon the Commissioner to treat this letter as an official complaint and to launch an investigation at the earliest opportunity.

Sincerely,

Nathalie Des Rosier

General Counsel

Appendix C: Summary of Findings and Recommendations

Findings:

Finding No. 1: The RCMP planning process was robust and thorough. The Commission found no indication that planning was influenced by anything other than legitimate security concerns.

Finding No. 2: The Commission saw no indication that security zones were created or sized to ensure that protesters were kept farther away from Internationally Protected Persons than was necessary, or that RCMP decisions in their respect were based on any inappropriate considerations.

Finding No. 3: The Public Affairs Communications Team employed appropriate strategies to provide information to the public leading up to and during the Summits.

Finding No. 4: The official G20 Summit security website should have contained information regarding the Public Works Protection Act inasmuch as it would potentially affect the public.

Finding No. 5: The Commission found neither intent nor action on the part of the Community Relations Group to obtain intelligence aimed at preventing groups from having their issues heard.

Finding No. 6: Community Relations Group members' records were not consistently stored in the Event Management System database.

Finding No. 7: The Joint Intelligence Group (JIG) fulfilled its mandate by conducting intelligence investigations and preparing and/or contributing to analytical reports.

Finding No. 8: The JIG appropriately identified and assessed criminal threats to the Summits.

Finding No. 9: Human rights were appropriately considered by JIG management.

Finding No. 10: The Commission saw no indication that RCMP undercover operators or event monitors acted inappropriately or as agents provocateurs.

Finding No. 11: The RCMP did not make or assist in any arrests at Queen 's Park.

Finding No. 12: The RCMP did not make any arrests, nor was it involved in detaining the crowd at The Esplanade on June 26, 2010.

Finding No. 13: The RCMP Public Order Unit (POU) Commander involved in the kettling of individuals at Queen Street and Spadina Avenue on June 27, 2010, took reasonable steps to ensure that his orders were legitimate in the circumstances.

Finding No. 14: The RCMP POU members involved in the kettling of individuals at Queen Street and Spadina Avenue on June 27, 2010 acted reasonably in executing the orders from the Toronto Police Service Major Incident Command Centre.

Finding No. 15: The involvement of the RCMP POU members in the kettling of individuals at Queen Street and Spadina Avenue on June 27, 2010, while inconsistent with RCMP POU policy and training, which maintains that crowds should be provided an egress route, was reasonable under the circumstances.

Finding No. 16: The RCMP was not present outside the Prisoner Processing Centre on Eastern Avenue on June 27, 2010.

Finding No. 17: RCMP members did not participate in the June 27, 2010, arrests at the University of Toronto.

Finding No. 18: The Commission found no information to suggest that RCMP members were engaged in the unreasonable use of force.

Finding No. 19: The RCMP played no role in the planning for, or management of, incidents at or near the Eastern Avenue Detention Facility.

Recommendations:

Recommendation No. 1: That the RCMP more effectively integrate into its planning function for major events an awareness of the possibility of ex post facto review and adopt commensurate document organization practices and guidelines for appropriate disclosure.

Recommendation No. 2: That the RCMP reflect in its agreements with other police agencies, to the extent possible, that RCMP note-taking guidelines require members to retain notes for, among other things, subsequent review of their conduct.

Recommendation No. 3: That all contacts be recorded and reported in a comprehensive and consistent manner to ensure proper and adequate recording of actions taken.

Recommendation No. 4: That the RCMP ensure that a formal, integrated post-incident process is established for all major events to ensure that deficiencies as well as best practices are identified.

Recommendation No. 5: That the RCMP consider the establishment of an enhanced approval and reporting structure for sensitive sector criminal intelligence investigations as a best practice for future major events where such investigations are contemplated.

Recommendation No. 6: That the RCMP develop and implement policy requiring best efforts to be made respecting entering into comprehensive agreements with other police agencies prior to beginning integrated operations, addressing such issues as command structure, strategic, tactical and operational levels, and the operation and application of policies and operational guidelines.

Recommendation No. 7: That the RCMP make best efforts to establish, together with its partners, clear operational policies prior to an event where integrated policing will occur to ensure consistency of application.

Appendix D: Legal Opinion: Jurisdiction of Authority at the 2010 G8/G20 Summits

Executive Summary

Security for the June 2010 Summit in Toronto was principally provided by the RCMP and TPS (Toronto Police Force), with the support of other police forces.

IPPs (Internationally Protected Persons) were protected by a series of concentric rings:

- CAZ ("Controlled access" zone) in the middle

- RAZ ("Restricted access" zone) beyond that

- IZ ("Interdiction zone") beyond that

- OZ ("Outside zone") beyond that.

The (federal) Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act:

- gives "primary responsibility" to the RCMP for security of intergovernmental conferences

- the RCMP "may take the appropriate measures, including controlling, limiting or prohibiting access to any area and to an extent and in a manner reasonable in the circumstances", but not to be "read as affecting the powers that peace officers possess at common law or by virtue of any other federal or provincial Act or regulation".

The (provincial) Public Works Protection Act expands police powers of provincial jurisdiction in or around a "public work", including search and arrest without warrant in or approaching a public work; the Government of Ontario passed a regulation defining a certain G20 area as a public work.

There are three points on the continuum of police empowerment:

- no authority to act

- authority to act

- required to act.

RCMP officers

- are peace officers for every part of Canada

- have "all the powers, authority, protection and privileges that a peace officer has by law"

- may enforce provincial laws where they are employed.

This authority is not exclusive, but concurrent with the police of (local) jurisdiction.

Ontario provincial police officers have authority anywhere in Ontario.

A municipal police force in Ontario (e.g. TPS) is required to act within their municipality.

With regard to swearing in RCMP officers as special constables:

- they are then able to enforce Ontario law

- they can enforce the laws in the province (or territory) if the officer is "employed" in that jurisdiction, which is understood to mean not the classic employer-employee relationship, but a jurisdiction with whom the RCMP has a (contractual) arrangement

- there is no RCMP-Ontario arrangement, so RCMP officers are not "employed" in Ontario, and do not have that type of consequential authority to enforce Ontario law

- however, swearing in RCMP officers as special constables (pursuant to Ontario's Police Services Act gives that authority).

Terms of deployment between police forces are generally expressed in a MOU (memorandum of understanding),which would indicate whose command, legislation, policy and operational guidelines deployed personnel are subject to.

Swearing in as special constables under the (Ontario) Interprovincial Policing Act, is a different situation, as RCMP officers are statutorily excluded from same.

The provincial disciplinary exposure of a special constable is different from that of a "full" police officer.

For constitutional law reasons, as well as statutory authority, there remain grey division lines between:

- exclusive versus concurrent jurisdiction

- responsibility,

which lines could be clarified in an express MOU between the RCMP and police of jurisdiction.

Though there was a Command and Control Document (C2 Document) and a Strategic Concept of Operations (SCO Document) there was no RCMP-TPS MOU to cover what was missing, including:

- neither police force relinquished their respective authority or responsibility

- the RCMP had primary, but not exclusive, responsibility

- the TPS remained the police force of jurisdiction, with the assistance of the RCMP and other forces.Footnote 1

In addition, no formal "arrangement" per the Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act was entered into between Canada and Ontario, the reason given that existing mutual support and efforts among security partners was already "outstanding".

The constitutional doctrine of paramountcy indicates that when federal-provincial division of powers is imprecise, resulting in overlapping laws within the competence of their respective legislators, the federal law will prevail to the extent of the inconsistency. An alternative doctrine called 'interjurisdictional immunity' is now regarded as having very limited application. Indeed, in the PHS Community Services Society decision of September 30, 2011, the Supreme Court of Canada emphasizes that the more flexible concepts of double aspect and cooperative federalism permit significant overlap between federal and provincial areas of jurisdiction, making recourse to either doctrine less likely.Footnote 2

The Command and Control (C2) Document was signed by all security partners, whereby the RCMP is:

- responsible for overseeing security planning and operations

- co-ordinating operational security requirements

- lead security agency

- responsible for operational resolution of any 'incidents', and

- retained overall responsibility

The Strategic Concept of Operations ("SCO") Document was prepared (by the RCMP) as an internal strategic planning guide, and does not appear to have been the subject of any specific agreement with security partners, though does describe the RCMP as being the "lead agency".

Though RCMP officers could have been authorized to enforce provincial laws in any and all zones (by being sworn in as special constables pursuant to the Ontario Police Services Act) we understand they were only deployed as special constables:

- during the June 20-23, 2010 pre-summit period

- prior to the security perimeter coming into effect June 25, 2010.

There is no judicial consideration of "primary responsibility" to assist in interpreting same in the context of joint police operations, though it may be that "primary responsibility" contemplates other security partners having "secondary responsibility".

The RCMP were required to control and act in both the CAZ and RAZ. Had a threat to Summit security or IPPs have manifested itself in the IZ or OZ, the RCMP would equally be required to act.

One police force does not have the power to direct another (police) force. Inter-police work is a matter of cooperation and agreement - the C2 Document both recognizes the RCMP's lead responsibility, including authority to direct, (in the CAZ and RAZ, not the IZ and OZ) and the relative responsibilities. The TPS, through the police jurisdiction, agreed to the command authority established by the RCMP.

Because it is not clear whether statutory provisions confer authority or requirement on the RCMP to direct other forces, the C2 Document is left as the only source of authority and requirement. It can be questioned whether the C2 Document is legally enforceable by any signatory. The C2 Document also expressly provides each police force (provincial, regional, municipal) retains their responsibilities as police of jurisdiction.

Protection of IPPs and securing international summits is a federal jurisdiction.

There is some authority for the principle that police forces have a professional and binding obligation to cooperate.

TPS is, and it was agreed, that the TPS

- was the police of jurisdiction in Toronto

- would "support the RCMP in its federally legislated mandate".

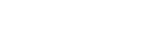

The TPS:

- was authorized and required to act in the CAZ and RAZ though did not have primary responsibility and was required (pursuant to the C2 Document) to follow RCMP direction

- was authorized and required to act in the IZ and OZ.

The TPS:

- was not authorized to direct the RCMP in the CAZ and RAZ

- was authorized to direct the RCMP in the IZ and OZ, by agreement.

As to regulatory codes of conduct, each force remains bound by their own, irrespective of which zone they were policing in – for example, even if the RCMP officers were operating under the direction of TPS in the IZ or OZ.

As the G20 area was designated as a "public work":

- peace officers (provincial, municipal, and arguably federal) properly had the additional powers (to stop, search, refuse entry) conferred by the (Ontario) Public Works Protection Act ("PWPA")

- the PWPA does not impact (or conflict with) existing federal legislation providing authority and responsibility to the RCMP, as additional powers (to the extent applicable) are given, not inconsistent ones.

Background

During the G20 Summit in Toronto in June 2010, security was principally provided by the RCMP and the Toronto Police Service (TPS), with the support of other police services arranged for by the TPS (including the Ontario Provincial Police, Calgary Police Service, London Police Service.) Approximately 300 RCMP members were sworn as Special Constables under Ontario's Police Services Act, (PSA) to support the TPS with pre-Summit policing but most, including the members of public order units (commonly called "riot squads" or "tactical units") were not. Most RCMP members worked within the inner controlled access zones, however, the 300 noted above, as well as several public order units, were deployed in the Outside Zone (described below).

Internationally Protected Persons (IPPs) were protected by a series of concentric rings:

- The "controlled access zone" (CAZ) referred to the areas of downtown Toronto in which the G20 summit took place and in which most IPPs were housed. The CAZ was encircled by a fence.

- A second fence designating a "restricted access zone" (RAZ) was also erected, and encircled the CAZ, as well as hotels in which delegates were lodged, certain other locations, and certain transportation corridors between those areas.

- Encircling the CAZ and the RAZ was a third fence delineating the "interdiction zone" (IZ). The IZ was the outer security area as designated by the RCMP and its partner agencies during planning for the G20 Summit.

The term "outside area" shall be used to describe the area beyond the interdiction zone, being the "outside zone" (OZ).

In addition to the Criminal Code, other statutes and common law, certain statutory provisions confer specific powers on RCMP members when ensuring the security of IPPs. These include section 18 of the RCMP Act, section 17 of the RCMP Regulations 1988, section 6 of the Security Offences Act, and the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Internationally Protected Persons, including Diplomatic Agents.

The Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act (FMIOA )provides:

10.1 (1) The Royal Canadian Mounted Police has the primary responsibility to ensure the security for the proper functioning of any intergovernmental conference in which two or more states participate, that is attended by persons granted privileges and immunities under this Act and to which an order made or contained under this Act applies.

(2) For the purpose of carrying out its responsibility under subsection (1), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police may take appropriate measures, including controlling, limiting or prohibiting access to any area and to the extent and in a manner that is reasonable in the circumstances.

(3) The powers referred to in subsection (2) are set out for greater certainty and shall not be read as affecting the powers that peace officers possess at common law or by virtue of any other federal or provincial Act or regulation.

In Ontario, the Public Works Protection Act (PWPA) provides for a number of expanded powers that may be exercised in or around any area designated a "public work". Notably, a guard appointed under the Act or a peace officer is empowered to search and arrest without warrant within an area specified as a public work or on approach to that area. On June 2, 2010, the Government of Ontario passed regulation 233/10Footnote 3 pursuant to the PWPA defining the area within a certain perimeter as a public work for the purposes of the PWPA. The regulation was filed on June 14, 2010. The regulation was not publicized although it was posted on the Ontario government website e-laws on June 16. It was not Gazetted until July 3, 2010, after the event had terminatedFootnote 4. The regulation was revoked on June 28, 2010.

Issues

The Commission seeks a legal opinion with respect to the following questions:

- 1) To what extent are RCMP members (including those sworn as Ontario Special Constables) authorized and/or required to exercise police powers within each of the controlled access zone, restricted access zone, interdiction zone and outside area? To what extent are RCMP members authorized and required to direct local police within those zones?

- 2) To what extent are local police authorized and/or required to exercise police powers within each of the controlled access zone, restricted access zone, interdiction zone and outside area? To what extent are local police authorized and/or required to direct RCMP members (including those sworn as Ontario peace officers) within those zones?

- 3) Within each of the controlled access zone, restricted access zone, interdiction zone and outside area, and for both RCMP members (including those sworn as Ontario peace officers) and municipal police officers, does a particular police agency's policy (regarding acceptable standards of conduct) become paramount? Do police officers continue to be bound by the policies of their respective agencies?

- 4) What impact, if any, does the FMIOA or other relevant federal legislation have within the area designated a public work pursuant to the PWPA?

Scope of Opinion

This opinion is limited to answering the four specific questions, as stated above, in the context of the G20 Summit held in Toronto in June 2010.

This opinion is not a direct response to the complaint lodged by the Canadian Civil Liberties Association with the Commission, dated October 18, 2010, but rather a background legal advisory on issues of concern to the Commission. There is no intention, nor instruction, in our preparation of this opinion to evaluate the actual conduct of the RCMP or other police forces in discharging police duties during the G20 Summit.

Assumed Facts

Our assumptions include:

- a) In reaching the conclusion we have assumed/relied on the accuracy of the information provided in the reviewed documents.

- We assume that control of the CAZ and the RAZ was required to ensure the security for the proper functioning of the G20 Summit , and that control of the IZ and OZ was not required.

- b) We assume that a RCMP officer is "employed" in the sense of " the prevention....of offences against the laws in force in any province in which they may be employed" (s.18(a) of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act), where the officer is working in a province with which the RCMP has an arrangement under s.20 of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act.

- c)This is sometimes called "contract policing". There is no such arrangement in Ontario which has its own provincial and municipal police forces.

Qualifications

This opinion is subject to the following qualifications:

- a) This opinion is limited to the laws of Ontario and federal laws applicable therein.

- b) The information, estimates and opinions contained herein are obtained from sources considered to be reliable, however, no representation is made with regard to the reliability thereof.

- c) This opinion contemplates facts and conditions existing as of July 2011. Events and conditions occurring after that date have not been considered.

Discussion and Analysis

A. Basic Principles

The following principles are foundational to our analysis:

1) There is a continuum of empowerment of a police force, from no authority, to authority, to being required to act.

We see three points on the continuum of police force empowerment: 'no authority', 'authority', and 'required to act' between which the lines, to use a legal phrase more used in the U.S., are not always bright.

- We must understand what the different steps on the continuum are.

- No authority: e.g. A police officer from the Calgary police force has no authority to act Ontario (unless special measures are taken, such as swearing in as a special constable).

- Authority to act (or 'have jurisdiction'):

- RCMP have authority to act anywhere in Canada:

Statute

"9. Every officer and every person designated as a peace officer under subsection 7(1) is a peace officer in every part of Canada and has all the powers, authority, protection and privileges that a peace officer has by law..." [Emphasis added] (RCMP Act, s.9)

Cases

"10 In reviewing the scheme and object of The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act it clear that section 3 and section 9 of that Act operate to render the Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers part of a "police force for Canada" and peace officers "for every part of Canada" with "all the powers, authority, protection and privileges that a peace officer has by law". The language used by parliament is clear, broad and unambiguous as it was their obvious intention to create a police force that operates without jurisdictional barriers throughout the entire country of Canada. There is nothing in the scheme or object of The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act that derogates from that basic presumption. This court notes that when there is a limitation on their duties it is clearly stated. For example, section 18 of The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act limits the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to enforcing only the provincial laws of the province in which they are employed.

[...]

19 When examining [sic] Section 21 of The Police Act 1990 [of Saskatchewan] one notes there is no clear language to imply derogation from the rights of an R.C.M.P. peace officer. The Act simply states that the R.C.M.P. are responsible for policing when there is an agreement between the province and the federal government. It further states that they are not responsible for policing a municipality unless there is an agreement. They certainly do not use words that the R.C.M.P. officer cannot or shall not provide police services in the municipality. As well, given the ultra vires statute construction doctrine, it would not be appropriate for provincial legislation to take away powers given by Federal legislation. This court therefore reads the provincial legislation in a manner in which the legislature is not taken to have exceeded it's jurisdiction. Therefore clearly The Police Act must be read in context as providing a manner of funding policing not a manner of taking away jurisdiction granted to R.C.M.P. officers by The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act.

20 In coming to this conclusion the court is of a view that there is no good public policy reason for the R.C.M.P. to be excluded from operating in any specific geographic area. It would not make sense for the legislature to limit the opportunity for policing of a community by making sure that fewer police officers are able to act in any particular setting within the province." [Emphasis added] (R v Abrametz, (2000) 7 MVR (4th) 133 (Sask Prov. Ct.), paras. 10 and 18-20, affirmed in 2001 SKQB 129)

"34 Therefore, Cp. Popoff did have the lawful authority as a member of the RCMP to conduct the investigation of the accused's conduct and to make the breath demand, even though all of that occurred within the corporate limits of the City of Saskatoon, and when he was off duty. Neither the pertinent legislation nor the federal/provincial agreement act to preclude that nature of conduct, even in the absence of a specific policing contract between the RCMP and the City of Saskatoon." (R v Figley McBeth, 2004 SKPC 119, at para. 34)

"19 A member of the R.C.M.P. could make such a demand anywhere in Canada, as his territorial jurisdiction extends through out Canada under the R.C.M.P. Act, R.S.C. 1970, c. R-9." (R v Soucy, (1975) 23 C.C.C. (2d) 561 (N.B.C.A.) at para. 19)

- Note that this authority is not exclusive authority, but is rather concurrent jurisdiction with any other police force's local jurisdiction.Footnote 5

- Ontario provincial police officers have authority to act anywhere in Ontario:

Statute

"[42.](2) A police officer has authority to act as such throughout Ontario." (Ontario Police Services Act, s.42(2))

Cases

"Section 56 of the Police Act, R.S.O. 1980, c. 381 provides:

Every chief of police, other police officer and constable, except a special constable or a by-law enforcement officer, has authority to act as a constable throughout Ontario.

[Emphasis added by the court] This section alone clothes O.P.P. officers with jurisdiction province-wide". (R v Giancarlo, (1992) 36 M.V.R. (2d) 141 (Ont. C.A.) at para. 4)

- Required to act (or 'have responsibility' to act):

- A municipal police (e.g. TPS) is required to act within their municipality (e.g. Toronto):

Statute

"4.(1) Every municipality to which this subsection applies shall provide adequate and effective police services in accordance with its needs." (Ontario Police Services Act, s.4(1))

Cases

"[6] Section 19(1) of the Police Services Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.15 provides that the Ontario Provincial Police have the responsibility to provide policing services to municipalities, which do not have their own police force. Section 19(1) of the Police Services Act provides that the Ontario Provincial Police have the responsibility to provide policing services to municipalities, which do not have their own police force. Section 19(1) provides:

19.(1) The Ontario Provincial Police have the following responsibilities: 1. Providing police services in respect of the parts of Ontario that do not have municipal police forces other than municipal law enforcement officers.

[7] The City of Toronto has its own police force, and therefore the Ontario Provincial Police do not have the responsibility to provide policing in Toronto." [Emphasis added] (Foster v ADT Security Services Canada Inc., 2006 CarswellOnt 5157 (S.C.J.), affirmed in 2007 ONCA 653)

Please note that being required to act is also not an exclusive jurisdiction. Different police forces could theoretically be required to act in a particular situation.

- "Duty" can be an ambiguous word because it has different meanings in different contexts. Distinguish requirement to act:

"17. (1) In addition to the duties prescribed by the Act, it is the duty of members who are peace officers to: [...] (b) maintain law and order in the Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territories and national parks and such other areas as the Minister may designate;" (RCMP Regulations)

from having general duty to preserve the peace and enforce crime:

"18. It is the duty of members who are peace officers, subject to the orders of the Commissioner,

(a) to perform all duties that are assigned to peace officers in relation to the preservation of the peace, the prevention of crime and of offences against the laws of Canada [...]" (e.g. Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act)

Officers who are working their shift are also said to be "on duty". Because of the possible confusion with respect to the meaning of duty, it will be avoided. This document will instead use the more precise expressions of "do not have authority to act", "have authority to act" (or "have jurisdiction") and "required to act" (or "have responsibility").

2) The impacts of swearing in special constables

The swearing of RCMP officers as special constables has two potentially material impacts:

- The first impact of swearing in RCMP officer as a special constable is that they would be able to enforce the laws of Ontario.

- RCMP officers are peace officers in every part of Canada per s.9 of RCMP Act. However, section 18(a) of the RCMP Act states that RCMP officers are only empowered to enforce federal laws, unless the officer is "employed" in a particular province in which circumstances they may also enforce the provincial laws of that province.

"18. It is the duty of members who are peace officers, subject to the orders of the Commissioner,

(a) to perform all duties that are assigned to peace officers in relation to the preservation of the peace, the prevention of crime and of offences against the laws of Canada and the laws in force in any province in which they may be employed, and the apprehension of criminals and offenders and others who may be lawfully taken into custody;" (RCMP Act, s.18(a))

"[19 ...] It is of interest to note that by s. 18 of the said Act [the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act], R.C.M.P. constables are restricted in enforcing the laws in force in any province in that they are given jurisdiction only in relation to provincial laws of the province in which they are employed." (R v Soucy, (1975) 23 C.C.C. (2d) 561 (N.B.C.A.)

"[10 ...] This court notes that when there is a limitation on their duties it is clearly stated. For example, section 18 of The Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act limits the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to enforcing only the provincial laws of the province in which they are employed." R v Abrametz, (2000) 7 MVR (4th) 133 (Sask Prov. Ct.)

- We understand that "employed" in this context does not mean an employer-employee relationship. Rather, "in which they are employed" means only a province with which the RCMP has an "arrangement" under section 20 of the RCMP ActFootnote 6:

"Arrangements with provinces

20. (1) The Minister may, with the approval of the Governor in Council, enter into an arrangement with the government of any province for the use or employment of the Force, or any portion thereof, in aiding the administration of justice in the province and in carrying into effect the laws in force therein.

Arrangements with municipalities

(2) The Minister may, with the approval of the Governor in Council and the lieutenant governor in council of any province, enter into an arrangement with any municipality in the province for the use or employment of the Force, or any portion thereof, in aiding the administration of justice in the municipality and in carrying into effect the laws in force therein." (RCMP Act)

- The RCMP does not have an arrangement pursuant to section 20 with Ontario (in contrast to the arrangement the RCMP has with Alberta or Saskatchewan, for example). Therefore, RCMP officers are not "employed" in Ontario and do not have the authority to enforce provincial laws in Ontario.

- Swearing RCMP officers in as special constables under section 53 of Ontario's Police Services Act empowers RCMP officers with the additional authority to enforce Ontario's provincial laws.

"Appointment of special constables

By board

53. (1) With the Solicitor General's approval, a board may appoint a special constable to act for the period, area and purpose that the board considers expedient. R.S.O. 1990, c. P.15, s. 53 (1); 1997, c. 8, s. 33 (1).

By Commissioner

(2) With the Solicitor General's approval, the Commissioner may appoint a special constable to act for the period, area and purpose that the Commissioner considers expedient. R.S.O. 1990, c. P.15, s. 53 (2); 1997, c. 8, s. 33 (2).

Powers of police officer

(3) The appointment of a special constable may confer on him or her the powers of a police officer, to the extent and for the specific purpose set out in the appointment." (Police Services Act)

- Depending on the particular details of the appointment, section 53(3) of the Police Services Act can confer on the special constable the power to enforce provincial laws:

"48 Pursuant to the Police Services Act, R.S.O. 1990, c.P15, a police services board may appoint special constables. The power to appoint is provided for in section 53(1) of the Act. Section 53(3) of the Police Services Act provides that "the appointment of a special constable may confer on him or her, the powers of a police officer, to the extent and for the specific purposes set out in the appointment". Section 30 of the Agreement between the Police Services Board and the Toronto Transit Commission dated May 9, 1997, confers on the special constables the powers of a police officer to enforce a certain number of statutes that are listed in that section of the Agreement. Suffice it to say that these powers extend, among others, to the Trespass to Property Act, and to sections 146 and 149 of the Provincial Offences Act. Therefore, when reading the Trespass to Property Act as well as the provisions of the Provincial Offences Act that allow a police officer to make an arrest pursuant to the Provincial Offences Act, special constables of the TTC have the powers of a police officer." (Ye v Toronto Transit Commission, 2009 CarswellOnt 8512 (S.C.J.))

- In addition to any limitations stipulated in the appointment of RCMP officers pursuant to section 53(1) of the Police Services Act, the terms of deployment of RCMP to another police service (and vice versa) are typically expressed in a memorandum of understanding or agreement including whose command, legislation, policy and operational guidelines such deployed personnel will be subject to.

- Note that swearing in as a special constable is different than being appointed under the Interprovincial Policing Act. These are different legislative schemes, both of which confer the powers of a police officer in Ontario. However, RCMP officers are explicitly excluded from being appointed under the Interprovincial Policing Act:

"Definitions

1. In this Act, [...]"extra-provincial police officer" means a police officer appointed or employed under the law of another province or a territory, but does not include a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police;

[...]

Appointment

8. (1) The appointing official may make the requested appointment if he or she is of the opinion that it is appropriate in the circumstances for the extra-provincial police officer to be appointed as a police officer in Ontario." (Interprovincial Policing Act)

- The second impact of swearing in an RCMP officer as a special constable, is that the RCMP officer would become subject to the limited discipline set out for Ontario special constables. A special constable is not subject to the full discipline of a police officer under the Ontario Police Services Act. This is because of a combination of the PSA's definition of "police officer" and the scope of application of this statute's misconduct provisions per s.80.

- The PSA defines a "police officer" as excluding special constables.

"Definitions

2 (1) In this Act, [...]

"police officer" means a chief of police or any other police officer, including a person who is appointed as a police officer under the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, but does not include a special constable, a First Nations Constable, a municipal law enforcement officer or an auxiliary member of a police force;" [Emphasis added] (Ontario Police Services Act, s.2)

- The PSA states that only a "police officer" can be guilty of misconduct.

"Misconduct

80. (1) A police officer is guilty of misconduct if he or she [...]"

- The only discipline to which special constables are subject is much more general. It is contained in PSA s.25

"Actions taken, auxiliary member, special constable, municipal law enforcement officer

(4.1) If the Commission concludes, after a hearing, that an auxiliary member of a police force, a special constable or a municipal law enforcement officer is not performing or is incapable of performing the duties of his or her position in a satisfactory manner, it may direct that,

(a) the person be demoted as the Commission specifies, permanently or for a specified period;

(b) the person be dismissed;

(c) the person be retired, if the person is entitled to retire; or

(d) the person's appointment be suspended or revoked." [Emphasis added] (Ontario Police Services Act (s.25(4.1))

- Therefore RCMP officers sworn in as special constables would be subject to facing a hearing and potentially having their special constable status revoked, thus returning the officer to the RCMP to consider other discipline as the employer.

3) Inter-Police Cooperation

The Canadian model of policing with federal, provincial and municipal police forces that (Quebec aside) share the same common law police powers and duties, as codified or varied by statutory authority, not surprisingly leaves some grey division lines between areas of exclusive versus concurrent jurisdiction and responsibility. This may be unavoidable, Canada's constitutional fulcrum lying as it does somewhere between Britain's federally centred policing authority and the U.S. (by virtue of U.S. constitutional law) state centred policing authority.

In a nutshell, the provincial power over the administration of justice under s.92(14) of the Constitution Act, 1982 includes the provision of police services. Ontario established a provincial police force and certain municipal police forces (like the TPS) which can enforce the federal Criminal Code, provincial statutes and municipal by-laws. Federally, Canada has established a federal police force, the RCMP, which can police all federal statutes passed under various s. 91 heads of power, including offences under the Criminal Code. Only in those provinces where the RCMP is under contract to provide provincial or municipal police services (not Ontario or Quebec), is the RCMP authorized to enforce provincial statutes or municipal by-laws.

As a practical matter this means that large scale international events, and in this particular case the G20 Summit involving IPPs, necessarily entail consultation and cooperation between different levels of police forces. This means joint planning and collaboration on security arrangements in advance of such events and joint command structures and understandings in place to maintain overall security and to manage specific incidents during the event.

Depending on respective sources of jurisdiction and responsibility, one policy agency may take the lead and another play a supporting role, but they typically refer to each other as "partner agencies" or "security partners". This reflects mutual respect and a common purpose to maintain the peace and protect life and property during a highly charged international summit, always having regard to the Charter's guarantee of freedom of expression and other rights and liberties.

The SCO Document and the C2 Document leave no doubt that much planning and effort went into ensuring the security for the proper function of the G20, even if on relatively short notice, but in the end the G20 Summit security command structures and the roles of the RCMP and the TPS were premised on these basic understandings:

- Neither police force relinquished their respective authority or responsibility;

- Whilst the RCMP had primary responsibility to ensure the security for the proper functioning of the G20 Summit, this was not exclusive responsibility

- And whilst the TPS remained the police force of jurisdiction for the City of Toronto before, during, and after the G20 Summit, they were assisted in meeting the increased demands of the Summit by deployment of RCMP and other police forces

- No express Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was signed between the RCMP and TPS governing the period of the G20 Summit

- No formal "arrangements" within the meaning of s. 10.1(4) of the FMIOA were made between the federal Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, with the approval of Cabinet, and the Ontario government to facilitate consultation and cooperation between the RCMP and TPS re performance of duties assigned to peace officers in relation to s. 2 offences under the FMIOA .

Indeed as close to the June 26-27 Summit dates as June 11, the Deputy Minister of Public Safety (Canada) wrote the Deputy Minister of Community Safety (Ontario) to recognize the consultation and cooperation between all provincial and municipal security partners with the RCMP:

"Thank you for your correspondence of May 7, 2010, in relation to the Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act (FMIOA).

Consultation and cooperation between all security partners is, of course, critical for the success of the upcoming G8 and G20 Summits. Extensive security planning has taken place over the past year and a half. As a result, security preparation efforts are well-advanced and have been tested through several formal exercises amongst the security partners. Implementation of the integrated security plan by the respective police agencies will soon take place as the Summits are unfolding shortly.

I understand that, after further assessment and extensive discussions amongst officials and security partners, it was agreed that a separate FMIOA arrangements is not required for the Summits as it would not grant further authorities to local police of jurisdiction. In addition, it was also concluded that the current suite of powers and authorities that peace officers possess at common law or by virtue of any other federal or provincial Act or regulation were sufficient for the G8 and G20 Summits. Furthermore, the premise of the FMIOA provision, upon which a separate arrangement could be based, is to facilitate consultation and cooperation between the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and provincial and municipal police forces and such consultation and cooperation is already well advanced.

To date, the support and efforts demonstrated by provincial and municipal security partners have been outstanding. The Government of Canada looks forward to continued excellent cooperation with Ontario in securing and ensuring the success of the upcoming Summit."

4) Doctrine of Paramountcy and Interjurisdictional Immunity

(a) Paramountcy doctrine

The Constitution Act, 1867, divides legislative powers between the federal (s.91) and provincial (s.92) governments. This division of powers can be imprecise, resulting in overlapping federal and provincial legislation.

Assuming that both of the overlapping laws are within the competence of their respective legislators, when the overlapping laws are inconsistent determining which law applies is often resolved with the doctrine of "federal paramountcy". This doctrine states that the federal law will prevailFootnote 7.

Most recently the Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (Attorney General) v. PHS Community Services SocietyFootnote 8 stated:

[70] In summary, the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity is narrow. Its premise of fixed watertight cores is in tension with the evolution of Canadian constitutional interpretation towards the more flexible concepts of double aspect and cooperative federalism. To apply it here would disturb settled competencies and introduce uncertainties for new ones.

[71] In the case of a conflict between a federal law and a provincial law, the doctrine of paramountcy means that the federal law prevails to the extent of the inconsistency: Canadian Western Bank,at para. 69. ... The doctrine of federal paramountcy applies when there is operational conflict between a federal and provincial law, or when a provincial law would frustrate the purpose of a federal law.

Determining inconsistency between laws

The most obvious example of an inconsistency between laws is where both laws cannot be complied withFootnote 9. For example, if a provincial law allocated exclusive responsibility over a subject to one authority, and federal law allocated exclusive responsibility over the same subject, to a different authority, there would be an inconsistency. On the other hand, if one level of government legislates a standard, and the other government legislates a higher standard, meeting the higher standard also meets the lower standard, and the laws are not inconsistent.

A more subtle example of an inconsistency is where overlapping laws can both technically be complied with, but that such compliance would "frustrate the purpose" of the federal lawFootnote 10. In one caseFootnote 11, the federal government legislated that a person could be represented by a lawyer or a non-lawyer before a particular tribunal. The provincial legal legislation prohibited non-lawyers from representing a person before any tribunals. Both laws could be complied with by having a lawyer represent the party. The court found that while dual compliance was possible, some of the purposes of the federal Act were to make the tribunal more informal, accessible and speedy. Using only lawyers before the tribunal would defeat these purposes. The provincial law was therefore inconsistent with the federal law.

Provincial law is inoperative to the extent of the inconsistency

To resolve the inconsistency, federal paramountcy makes the provincial law inoperative. This means that the provincial law does not govern the topic that is the subject of overlapping laws. Non-compliance with the provincial law has no effect, whereas non-compliance with the federal law has its usual full effect.

It is important to note that provincial law is affected only insofar as it is inconsistent with the federal lawFootnote 12. This may mean the effect is quite narrow, such that a particular section of provincial law is inoperative for so long as the federal law is not repealed.

(b) Alternative solution: Interjurisdictional Immunity

The doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity means that one level of government cannot legislate in a way that impairs the "basic, minimum and unassailable content"Footnote 13 of a subject which s.91 allocates to the federal governmentFootnote 14, even when the legislation in general is constitutional.

While provincial governments have the constitutional power to legislate generally regarding subjects under s.92(13) (property and civil rights), that constitutional power cannot hinder federal constitutional powers. In the past this doctrine has meant that provincial laws requiring protective reassignment of pregnant workers did not apply to an interprovincial telephone companyFootnote 15, and that provincial labour laws have been inapplicable to postal workersFootnote 16.

This doctrine is discussed by the Supreme Court of Canada in PHS Community Services Society (released September 30, 2011)Footnote 17 and, described as having been narrowed, though not abolished, by recent jurisprudence, in favour of the "emergent practice of cooperative federalism, which increasingly features interlocking federal and provincial legislative schemes." The Chief Justice for a unanimous Court writes:

[58] The doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity is premised on the idea that there is a "basic, minimum and unassailable content" to the heads of powers in ss. 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 that must be protected from impairment by the other level of government: Bell Canada v. Quebec (Commission de la santé et de la sécurité du travail), [1988] 1 S.C.R. 749,at p. 839. In cases where interjurisdictional immunity is found to apply, the law enacted by the other level of government remains valid, but has no application with regard to the identified "core".

[59] It is not necessary to show that there is a conflict between the laws adopted by the two levels of government for interjurisdictional immunity to apply: Quebec (Attorney General) v. Canadian Owners and Pilots Association, 2010 SCC 39, [2010] 2 S.C.R. 536, at para. 52 ("COPA"). Indeed, it is not even necessary for the government benefiting from the immunity to be exercising its exclusive authority: Canadian Western Bank, at para. 34.

[61] Recent jurisprudence has tended to confine the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity. In Canadian Western Bank, the majority stated that "although the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity has a proper part to play in appropriate circumstances, we intend now to make it clear that the Court does not favour an intensive reliance on the doctrine, nor should we accept the invitation of the appellants to turn it into a doctrine of first recourse in a division of powers dispute" (para. 47). More recently, in COPA, the majority held that the doctrine "has not been removed from the federalism analysis", but rather remains "in a form constrained by principle and precedent" (para. 58).

[62] This caution reflects three related concerns. First, the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity is in tension with the dominant approach that permits concurrent federal and provincial legislation with respect to a matter, provided the legislation is directed at a legitimate federal or provincial aspect, as the case may be. This model of federalism recognizes that in practice there is significant overlap between the federal and provincial areas of jurisdiction, and provides that both governments should be permitted to legislate for their own valid purposes in these areas of overlap.

[63] Second, the doctrine is in tension with the emergent practice of cooperative federalism, which increasingly features interlocking federal and provincial legislative schemes. In the spirit of cooperative federalism, courts "should avoid blocking the application of measures which are taken to be enacted in furtherance of the public interest": Canadian Western Bank, at para. 37. Where possible, courts should allow both levels of government to jointly regulate areas that fall within their jurisdiction: Canadian Western Bank, at para 37.

[64] Third, the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity may overshoot the federal or provincial power in which it is grounded and create legislative "no go" zones where neither level of government regulates. Since it is not necessary for the government benefiting from the immunity to actually regulate in the field in question, extension of the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity risks creating "legal vacuums": Canadian Western Bank,at para. 44.

[65] While the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity has been narrowed, it has not been abolished. Predictability, important to the proper functioning of the division of powers, requires recognition of previously established exclusive cores of power: Canadian Western Bank,at paras. 23-24. Nor, in principle, is the doctrine confined to federal powers: Canadian Western Bank. However, in areas of overlapping jurisdiction, the modern trend is to strike a balance between the federal and provincial governments, through the application of pith and substance analysis and a restrained application of federal paramountcy. Therefore, before applying the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity in a new area, courts should ask whether the constitutional issue can be resolved on some other basis.

B. Issues

The Commission seeks a legal opinion with respect to the following questions:

To what extent are RCMP members (including those sworn as Ontario Special Constables) authorized and/or required to exercise police powers within each of the controlled access zone, restricted access zone, interdiction zone and outside area? To what extent are RCMP members authorized and required to direct local police within those zones?

a) RCMP authority or requirement to act in different zones

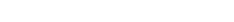

Text Version

RCMP authority and requirement to act at Toronto G20

The RCMP authority and requirement to act at Toronto G20 diagram is a pictorial depiction composed of concentric circles representing the RCMP responsibility to act within each of the Controlled Access Zone, Restricted Access Zone, Interdiction Zone and Outer Zone as identified in connection with the 2010 G20 Summit in Toronto. The innermost circle represents the Controlled Access Zone, while the next innermost circle represents the Restricted Access Zone. The depiction indicates that in both zones, the RCMP was authorized and required to act pursuant to subsection 10.1(1) of the Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act and subsection 6(1) of the Security Offences Act.

The two outermost concentric circles represent the Interdiction and Outer Zones respectively. The depiction indicates that in both zones, the RCMP was authorized to act pursuant to section 9 of the RCMP Act but, pursuant to subsection 4(1) of Ontario’s Police Services Act, was not required to do so.

- TPS retained their municipal policing responsibilities as the police force of jurisdiction.

- RCMP retained their authority and primary responsibility with respect to ensuring the security for the proper functioning of the G20 Summit and protection of IPPs. Therefore, if some threat to the security of the Summit or to IPPs had manifested in the IZ or OZ, the RCMP would equally be required to act in the IZ or OZ to address that threat, even though the threat was outside the RAZ and CAZ.

(i) Key Document Statements

C2 Document – Federal Responsibility and RCMP

The ISU-GIS 2010 Summits Command and Control (C2) Document is the 'capstone document' for command and control for the G20 Summit dated March 25, 2010, but finally signed as amended by all Integrated Security Unit (ISU) partner agencies on June 3, 2010.

The C22 Document outlines the role of the RCMP at the G20 Summit as follows:

"...the RCMP is responsible for overseeing security planning and operations as well as the coordination of operational security requirements with federal, provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies.

The RCMP, as the lead security agency, is mandated to provide protection to the visiting IPPs and security of the Sites. The RCMP will also provide support assistance to its policing partners. These services will be provided under the direction of the UCC Incident Commander. If a critical incident or terrorist activity occurs during the G8 or G20 Summit that would constitute a threat to the security of Canada or to an IPP, the UCC will ensure that immediate actions are taken to safeguard life and property.

In accordance with the Security Offences Act, the RCMP will be responsible for the operational resolution of the incident subject to the policy direction of the Government of Canada. The RCMP will also ensure, through the appropriate Government agencies/departments/services, that the National Counter Terrorism Plan is implemented.

The RCMP will ensure the democratic right of individuals to demonstrate peacefully while maintaining proper security. "

"As the Commanding Officer of the leading agency, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Commission retains overall responsibility for the 2010 G8 and G20 Summits and is responsible to the Government of Canada for the security and operations of the Summits.

SCO Document – RCMP Authority

The Strategic Concept of Operations G20 Summit June 26-27, 2010 document (SCO Document), prepared by the RCMP as an internal strategic planning guide to facilitate more detailed planning of the key security functions, does not appear to have been the subject of any specific agreement with partner agencies and, as such, has no express bearing on the question of RCMP and TPS authority or requirement to act in the various zones.

However, as a matter of internal record in advance of the Summit, it provides:

"The RCMP is Canada's national police service, and the sole agency with federal policing jurisdiction. The RCMP derives its authority from the RCMP Act, and takes direction from the Minister of Public Safety. The RCMP is mandated to provide security and to ensure the safety of Canadian dignitaries, Internationally Protected Persons (IPPs), designated sites, and Major Events.

The RCMP has been tasked as the lead agency responsible for the security of the G8 Summit. The knowledge and practices relevant to safeguarding visiting heads of state and foreign diplomats resides with the RCMP's Protective Policing Branch. 'O' Division has the responsibility of delivering the operational requirements for the G8 Security."

And further that:

"The RCMP is the lead and supported agency for Security of the Summit. RCMP will work in close partnership with federal partners and police services of jurisdiction within the province."

"The RCMP is responsible for the security and movement of Internationally Protected Personnel (IPP)."

"The RCMP will establish Controlled Access Zones (CAZ) in relation to venues and as required. The RCMP will establish Controlled Access Zones (CAZ) in relation to venues and as required. The RCMP will direct the establishment of additional security zones to be policed by supporting security partners as required."

(ii) Where the RCMP were authorized to act

- RCMP officers are peace officers in every part of Canada (RCMP Act s.9).

- RCMP are authorized to exercise all common law and statutory powers of peace officers with respect to enforcing federal laws across CanadaFootnote 18, including all zones in Toronto during the G20.

- However, unless appointed as Special Constables in Ontario RCMP officers would not be authorized to enforce provincial laws in any zone because the RCMP is not employed in OntarioFootnote 19.

- Depending on the details of appointment as a special constable, RCMP officers could have been authorized to enforce provincial laws in any or all zones by virtue of appointment as special constables and the powers thereby conferred under s. 53(3) of the Police Services Act. We understand though that RCMP were only deployed as special constables during the pre-Summit period of June 20-23, 2010, and prior to the security perimeter coming into effect on June 25.

(iii) Where the RCMP were required to act

- The RCMP is not responsible for enforcing all laws across Canada because the provinces have the power to establish provincial and municipal police forces responsible for enforcing provincial laws and municipal by-laws (Constitution Act 1867, s.92(14)).

See also the a contrario implication from Royal Canadian Mounted Police Regulations sections 17(1)(a) and (b):

"17. (1) In addition to the duties prescribed by the Act, it is the duty of members who are peace officers to [...]

(b) maintain law and order in the Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territories and national parks and such other areas as the Minister may designate;

(c) maintain law and order in those provinces and municipalities with which the Minister has entered into an arrangement under section 20 of the Act and carry out such other duties as may be specified in those arrangements;"

- The RCMP had primary responsibility to ensure the security for the proper functioning of the Summit per FMIOA s.10.1(1)

"10.1 (1) The Royal Canadian Mounted Police has the primary responsibility to ensure the security for the proper functioning of any intergovernmental conference in which two or more states participate, that is attended by persons granted privileges and immunities under this Act and to which an order made or continued under this Act applies."

- The RCMP were also required (had primary responsibility) to protect IPPs per Security Offences Act s.6(1):

"6. (1) Members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who are peace officers have the primary responsibility to perform the duties that are assigned to peace officers in relation to any offence [where the victim is an IPP] referred to in section 2 or the apprehension of the commission of such an offence."

- The RCMP is also required to protect IPPs pursuant to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Regulations section 17(1)(f)(i):

"17. (1) In addition to the duties prescribed by the Act, it is the duty of members who are peace officers to [...]

(f) protect, within Canada, whether or not there is an imminent threat to their security,