Interim Report on Chairperson-initiated Complaint and Public Interest Investigation regarding Policing in Northern British Columbia

PDF Format [2.22MB]

Related Links

- News Release

February 16, 2017 - Backgrounder

February 16, 2017 - Final Report

February 16, 2017 - Commissioner's Preliminary Review

16 July, 2016 - Commissioner's Response

March 9, 2016 - Chair-Initiated Complaint

May 15, 2013

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Background

The RCMP provides policing services under contract to the province of British Columbia, serving as the provincial police force. It is the largest RCMP division, providing local police services to several large municipalities, as well as all municipalities with a population under 5,000 and unincorporated areas throughout the province, including many First Nations communities. The RCMP polices the northern part of the province, referred to as North District, out of 35 detachments, as well as satellite offices.

For a number of years, concerns have been raised by individuals and various human rights and civil liberties organizations about policing in northern British Columbia, including a 2011 report by the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association,Footnote 1 the 2012 report of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, led by the Honourable Wally T. Oppal,Footnote 2 and a 2013 report by Human Rights Watch.Footnote 3 These reports, as well as specific police-related incidentsFootnote 4 in northern British Columbia, garnered significant media and public attention.

Public Interest Investigation

Police accountability contributes to police legitimacy, underpinning public support for law enforcement. As such, the Interim Chairperson (now Chairperson) of the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMPFootnote 5 (the Commission) considered the concerns expressed in these various reports and determined it was in the public interest to initiate a complaint and an investigation into the conduct of RCMP members involved in carrying out policing duties in northern British Columbia.

This public interest investigation focused exclusively on the RCMP's North District, as this is the region where many of the expressed concerns centered. The Commission examined RCMP member conduct relating to the policing of public intoxication; the incidence of cross-gender police searches; the handling of missing persons reports; the handling of domestic violence reports; the use of force; and the handling of files involving youth.Footnote 6

WHO WE ARE

The Commission is an independent agency created by Parliament to ensure that public complaints made about the conduct of RCMP members are examined fairly and impartially. The Commission is not part of the RCMP.

Commission reports make findings and recommendations aimed at correcting and preventing recurring policing problems. The Commission's goal is to promote excellence in policing through accountability.

In an effort to determine whether any systemic policing issues existed in northern British Columbia, the Commission conducted separate investigations for each of the designated areas, with the exception of youth files,Footnote 7 setting out to determine whether relevant RCMP policies, procedures and training are adequate. Moreover, an extensive file review of RCMP North District occurrence reports and use of force reports was conducted.

Investigation Results

The Commission's mandate, being remedial in nature, aims to identify any improvements that could be made, if appropriate, with the goal of satisfying the public's interest in enhancing and maintaining confidence in the national police force. As such, following an extensive investigation involving several investigators, numerous interviews, and the review of over 100,000 pages of documentation, the Commission made 45 findings and 31 recommendations:- 10 recommendations regarding personal searches;

- 6 recommendations regarding public intoxication;

- 4 recommendations regarding use of force reporting;

- 5 recommendations regarding domestic violence; and

- 6 recommendations regarding missing persons.

A complete list of the Commission's findings and recommendations can be found in Appendix A.

In summary, the Commission found deficiencies or lack of clarity in policies related to personal searches, policing of public intoxication, and missing persons. The Commission also found room for improvement in domestic violence and use of force reporting policies. Recommendations to strengthen and improve the policies were made, including but not limited to:

- amending national and divisional policies related to personal searches to provide more clarity, reflect current jurisprudence and improve transparency;

- amending national policy related to the arrest of young persons to include guidance to members on notification requirements when a youth is arrested and held in custody without charge;

- amending divisional policy which guides members on conditions for release in public intoxication cases, including consideration of alternatives to detention; and

- amending national policy on missing persons to include on operational files a full articulation of risk assessments, as well as documented observations and direction of supervisors.

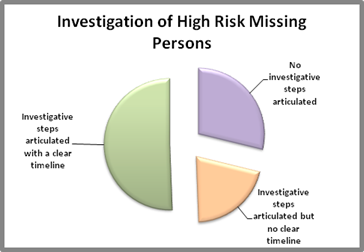

In reviewing occurrence reports and use of force reports, the Commission also found issues with policy compliance, including many instances of inadequate articulation—a key component of police accountability. For example, nearly half of the missing persons reports reviewed by the Commission failed to show that the RCMP in the North District investigated cases promptly and thoroughly, as per policy. That is not to say that these cases were improperly investigated but that the Commission was unable to determine if policy was followed due to the lack of adequate notation on the occurrence reports.

In general, most of the Commission's recommendations are aimed at enhancing transparency and accountability through improved policies and procedures, enhanced supervisory review, better reporting, and improved training.

Community and RCMP Engagement

As part of the established Terms of Reference, the Commission also undertook to engage community and RCMP members in northern British Columbia to allow residents and the police to be heard. Interested community representatives and RCMP members were asked to share their views and experiences in relation to the specific areas identified (public intoxication, personal searches, missing persons, domestic violence, use of force, and youth) as well as policing in general in the north of the province.

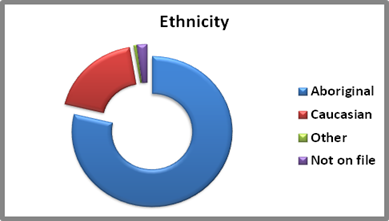

Given the many concerns expressed by human rights and civil liberties groups about police treatment of Aboriginal persons, a focus was placed on interviewing Aboriginal leaders. The Commission travelled to 21 communities in northern British Columbia, interviewing 64 community members (including some representatives of human rights and civil liberties organizations) and 32 RCMP members. Statements were made on a confidential basis, allowing participants to speak openly and with candor. The observations made reflected the experiences and/or perceptions of the individuals and are not necessarily the shared views of the communities, the RCMP or the Commission.

The engagement efforts provided individuals with an opportunity to raise specific concerns, if any, regarding RCMP member conduct, as well as to raise awareness of the role of the Commission and the public complaint process in general. Any individual complaints arising from this process would have been handled separately from the public interest investigation; however, no such complaints were made.

Given that much of the information gleaned from the community and RCMP member engagement was anecdotal and unsubstantiated, the Commission made no findings or recommendations based on the outcomes of community engagement. However, the results are important to note, as they represent the views and suggestions of some northern British Columbia residents, as well as RCMP members policing the region.

From the perspective of many community members interviewed by the Commission, the general perception of the RCMP in smaller or rural communities was positive. The Commission was told of the good relationship between RCMP members and the communities they police, particularly those with a dedicated First Nations policing member. The largely positive impression was often attributed to the efforts made by RCMP members in smaller communities to develop relationships with the residents and integrate into the community. The same was not said of the RCMP in larger, urban communities, where the perception was that RCMP members do not dedicate the necessary time to relationship-building. RCMP members also highlighted the importance of good community relations, and some suggested that an urban-based First Nations policing program or Aboriginal policing strategy was needed to provide a form of enhanced policing in the urban areas of northern British Columbia.

Community and RCMP members also commented on police leadership as a determining factor in the quality of relationships between the community and the RCMP. Detachment commanders were noted as taking the lead in forging community relationships in smaller communities. In larger communities, the leadership was viewed as setting the tone for member interaction with the public, leaving individual RCMP members to establish relationships.

In that regard, the Commission saw evidence of RCMP progress in putting suitable members in leadership positions in the North District, as demonstrated by the many positive comments from First Nations communities about local detachment commanders. In particular, the RCMP appears to have made an effort to assign culturally sensitive detachment commanders with significant experience dealing with First Nations communities to areas with high Aboriginal populations. However, the frequent turnover of RCMP members, including detachment commanders, was a common criticism of community members.

Another issue of note made by several community members, particularly in larger urban communities, was the perception of racism towards Aboriginal and First Nations persons by the RCMP—and by society more broadly. Certain individuals spoke of the distrust Aboriginals have for the police, citing the historical role of the RCMP in apprehending children to be sent to residential schools as a general factor.

Finally, some community representatives offered suggestions for improving RCMP policing in the region, including: providing members with cultural awareness training with a local focus; and committing additional police resources to the region, such as more officers and dedicated units (e.g. domestic violence).

North District public complaints

As noted above, no public complaints were received as a result of the Commission's community engagement efforts as part of this public interest investigation. The Commission acknowledges that there may be some reluctance on the part of some community members to make a complaint. That said, a number of complaints were made during the period under review.

Based on information provided by the RCMP, 792 public complaints were received regarding detachments in British Columbia RCMP's North District, between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2012. This compares to a total of 5,111 complaints for the Division and 10,949 complaints for the RCMP Force-wide. North District complaints represented 15.5% of all complaints in the Division for that time period.Footnote 8

The main allegations raised in the North District complaints are shown in the table below and are compared to those for the RCMP in British Columbia and Force-wide:

| Top Three Allegations | North District RCMP (number | %) |

RCMP in British Columbia (number | %) |

Force-Wide (number | %) |

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Neglect of Duty |

Neglect of Duty |

Neglect of Duty |

2 |

Improper Attitude |

Improper Attitude |

Improper Attitude |

3 |

Improper Use of Force |

Improper Use of Force |

Improper Use of Force |

In response to the 792 complaints in the North District, the RCMP:

- issued 418 (52.7%) letters of disposition; Footnote 9

- terminated 14 complaints (1.8%); and

- informally resolved 360 (45.4%) complaints.Footnote 10

A complainant who is not happy with the RCMP's response to his/her complaint (as noted in the Letter of Disposition) may refer the complaint to the Commission for review. Of the 418 complaints where letters of disposition were issued, the Commission received 38 requests for review.

During that time period, the Commission also conducted five Chair-initiated complaints and/or public interest investigationsFootnote 11 in relation to incidents in the North District. For example, the Chairperson initiated a complaint and investigated the 2008 in-custody death of Ms. Cheryl Anne Bouey in Prince George; the 2009 shooting death of Mr. Valeri George in Fort St. John, as well as a 2011 incident involving the use of a conducted energy weapon (CEW) on a child in Prince George. A public interest investigation was also conducted into a 2011 use of force incident in Williams Lake involving a 17-year-old girl. The Chairperson also initiated a complaint and public interest investigation into the 2012 shooting death of Mr. Gregory Matters.Footnote 12

Conclusion

The public interest investigation set out to determine whether any systemic problems existed in the RCMP's policing of missing persons cases, publicly intoxicated persons, use of force, domestic violence and personal searches in northern British Columbia. The Commission placed a particular focus on transparency and accountability in reviewing operational policies and procedures, examining the role of supervisors, and reviewing documented articulation of member actions.

Although thousands of occurrence reports and numerous policies and procedures were reviewed in the course of the investigation, in addition to several interviews of RCMP members and other stakeholders, it did not result in findings of broad, systemic problems with RCMP actions in northern British Columbia in relation to the issues under examination.

The evidence did, however, point to policy and reporting weaknesses, compliance issues and the need for more robust training and supervision. In that regard, two issues consistently emerged from the public interest investigation: inadequate articulation of police actions on occurrence or use of force reports, and inconsistent supervisory review of case files. In addition, the Commission's personal search and use of force investigations identified important shortcomings in reporting practices that seriously impedes or limits independent review.

RCMP policy is clear on the importance of completeness and quality of file content, including member articulation, in occurrence records management systems (e.g. the Police Records Information Management Environment [PRIME], which is used in British Columbia). Members are accountable for the data on occurrences to which they are assigned, while supervisors and commanders are accountable for the completeness and accuracy of that data. However, the Commission found several instances of non-compliance with policies on articulation in the areas examined.

Supervisory review was another issue that emerged. Inadequate supervisor review was manifested in the high proportion of files that were not fully compliant with policy guidelines and/or the general absence of indications of supervisor comments or direction in files, such as those for missing persons. The importance of effective supervision was emphasized throughout the Commission's investigation.

Finally, the Commission faced challenges with systems and procedures that did not support or otherwise facilitate external review. For example, the Commission intended to conduct a file review to examine member compliance with RCMP personal search policies and procedures—including instances of strip searches. However, the Commission was informed that the RCMP records management system in British Columbia does not track or otherwise account for the frequency or type of searches conducted, nor does the system allow for a recording of searches by members of the opposite sex (i.e. cross-gender searches). While this information may be recorded in a member's notebook, the lack of systematic recording or tracking severely limited the Commission's ability to evaluate compliance or determine if a systemic issue existed in this regard. The Commission has previously reported on ". . . the importance of appropriate document management and storage, so as to facilitate later review."Footnote 13 However, it remains an ongoing problem, which is not insignificant, as it directly affects RCMP accountability. As such, several of the recommendations made in this report are aimed at enhancing RCMP transparency and accountability, which form the cornerstones of public trust in the police.

Although the Commission's community engagement reflected a certain level of satisfaction with the RCMP particularly in rural areas, there remained a perception by many community members that the RCMP is biased against Indigenous people. Despite the Commission being unable to substantiate that view through its policy and file review, the Commission acknowledges that the noted weaknesses in some policies and procedures may affect the overall transparency and accountability of the RCMP, which in turn can foster distrust and feed community perceptions that often reflect an individual's personal experiences.

Introduction

In keeping with the Commission's mandate, this investigation aims to identify any systemic policing issues in northern British Columbia. The results are set out in this report, comprising of five parts:

- Part I: Scope of Public Interest Investigation

- Part II: Context

- Part III: Investigation

- Part IV: Community and Member Engagement

- Part V: Conclusion

The report was prepared following an extensive investigation by several investigators, who examined:

- relevant RCMP operational policies and procedures;

- relevant training documents from the RCMP Training Academy (Depot Division) Cadet Training Program, the RCMP's Pacific Region Training Centre, and the Field Coaching Program, as well as other training and information resources available to British Columbia RCMP members;

- over 4,000 police occurrence reports and 301 Subject Behaviour/Officer Response reports from the North District;

- applicable legislation and case law; and

- inquiry reports, reports from human rights and civil liberties organizations, policies and procedures from other police jurisdictions, coroners' inquests reports, academic research, and relevant policy and training documents from the Government of British Columbia.

As a means of evaluating policy compliance as well as the adequacy of training, the Commission undertook a file review of occurrence reports in relation to missing persons, public intoxication and domestic violence investigations, as well as use of force reports. The reports were reviewed in detail to determine whether any systemic issues existed and if the documents demonstrated that RCMP members had followed relevant policies and procedures. In most cases, the Commission evaluated the completeness of records, the quality of member articulation and investigative steps, and quality control indicators, such as evidence of supervisor review.

Supplementing the examination of policies, procedures, training and RCMP occurrence reports, the Commission interviewed 84 people, including RCMP members from:

- National Headquarters;

- British Columbia Headquarters;

- North District; and

- Pacific Region Training Centre.

Other subject matter experts, such as academics and employees of the Government of British Columbia, were also interviewed.

Part I: Scope of Public Interest Investigation

On May 15, 2013, in consideration of concerns raised by human rights and civil liberties organizations with respect to policing in northern British Columbia, the Interim Chairperson (now Chairperson) of the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP (the Commission) initiated a complaint and public interest investigation into the conduct of RCMP members involved in carrying out policing duties in northern British Columbia, pursuant to the authority granted to the Commission by subsections 45.37(1) and 45.43(1) of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act (RCMP Act)—in force prior to November 28, 2014.

The established Terms of Reference set out to examine and report on RCMP member conduct relating to the following specific areas:Footnote 14

- the policing of public intoxication;

- the incidence of cross-gender police searches;

- the handling of missing persons reports;

- the handling of domestic violence reports;

- use of force; and

- the handling of files involving youth.

The Commission conducted separate investigations for each of these designated areas, with the exception of youth files.Footnote 15 Each investigation set out to determine whether relevant RCMP policies, procedures and training are adequate, and whether any systemic issues could be identified.

Policies and procedures related to public intoxication, personal searches, missing persons, domestic violence, and use of force were examined in detail and assessed on:

- consistency with law and current jurisprudence;

- clarity of guidance to members;

- consistency between national and divisional policies; and

- provisions made for accountability and quality control.

The Commission is an independent agency of the Government of Canada mandated to conduct an objective examination of the evidence gathered during its investigation and, where appropriate, make recommendations to improve conduct by RCMP members. A summary of the Commission's 45 findings and 31 recommendations can be found in Appendix A.

In support of the public interest investigation, interested community members and RCMP employees were interviewed in an effort to obtain information regarding the specific areas identified in the Terms of Reference, as well as policing in northern British Columbia more broadly. The interviews allowed individuals to raise specific concerns, if any, regarding RCMP conduct. The community and RCMP engagement further provided the opportunity to raise awareness of the role of the Commission and the public complaint process in general. Any specific individual complaints arising during the course of the investigation would have been handled as separate public complaints.Footnote 16 For more information about the public complaint process and complaints about the RCMP in the North District, please refer to Appendix B.

The Commission has considered all of the above issues, materials and insights provided therein. As contemplated by subsections 45.76(1) and 45.76(3) of the RCMP Act, the Commission's report is prepared ad interim and requires the RCMP Commissioner to review and respond before a final report is submitted to the Minister.

Part II: Context

Concerns Alleged by Human Rights and Civil Liberties Organizations

In 2011, the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association issued a report on policing in northern British Columbia entitled SMALL TOWN JUSTICE: A report on the RCMP in Northern and Rural British Columbia. The report raised concerns about differential treatment of Indigenous people, inappropriate use of force, treatment of youth, retaliation for complaints, lack of accountability, understaffing and high staff turnover in RCMP detachments.Footnote 17

Subsequently, the 2012 report of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, led by the Honourable Wally T. Oppal, detailed specific areas of police systemic failure, including failure to follow investigative and case management guidelines; ineffective inter-agency coordination; and poor accountability. The inquiry found systemic bias in the police with regard to the missing women, lack of leadership and oversight, inadequate policing policies and practices and so on.Footnote 18 The issues raised by the Commission of Inquiry were repeated in the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in British Columbia, Canada (2014).Footnote 19

In its 2013 report entitled Those Who Take Us Away: Abusive Policing and Failures in Protection of Indigenous Women and Girls in Northern British Columbia, Canada,Footnote 20 Human Rights Watch alleged that police in northern British Columbia have been generally abusive with regard to policing Indigenous women and girls and have broadly failed to protect Indigenous women and girls. It also alleged a lack of confidence among this population in the ability and willingness of police to protect them, stemming from poor or non-existent police response to disappearances and murders, and inadequate police action in response to domestic violence and sexual assault. That report also made allegations regarding apparent shortcomings of oversight mechanisms designed to provide accountability for police misconduct.

Policing in British Columbia

Known administratively as "E" Division, the RCMP in British Columbia has over 9,500 employees and is the largest RCMP division in the country.

The Division is divided into four districts: Vancouver Island District; Lower Mainland District; South East District; and North District.

The Commission's public interest investigation focused exclusively on the North District, headquartered in Prince George. North District polices approximately 70 percent of the province's land area and includes 35 RCMP detachments, plus satellite support units, with 664 members and 75 public service employees.Footnote 21

Policing the Aboriginal population and First Nations communities deserves specific attention in any discussion of policing in northern British Columbia. Aboriginal people represent 5.4% of British Columbia's total population and 17.5% of northern British Columbia's population.Footnote 22 The Aboriginal population, in urban centres and off and on reserves, forms a higher percentage of the total population in northern British Columbia than in the southern regions of the province. In the urban centres in the North District and in off-reserve rural areas, the RCMP provides police services to the Aboriginal population as part of the overall population. On the reserves, many communities are policed by officers assigned under the First Nations Community Policing Services.

In 2012, the First Nations Community Policing Services had an authorized strength of 108.5 RCMP officers who provided dedicated police services to 131 First Nations communities in British Columbia through 53 community tripartite agreements. These agreements are negotiated among First Nation or Inuit communities, provincial or territorial governments, and the federal government. Under a community tripartite agreement arrangement, the First Nation or Inuit community has dedicated officers from an existing police service, typically the RCMP.Footnote 23 The majority of detachments in the North District have one or more authorized positions for First Nations Policing officers.

Part III: Investigation

The following sections summarize the Commission's investigation into each of the areas designated in the Terms of Reference (personal searches, policing of public intoxication, use of force, domestic violence, and missing persons). Police interaction with women and youth are addressed within each investigation, where feasible.

Personal Searches

Context

In Canada, police authority to search a person, incidental to a lawful arrest, derives from common law.Footnote 24 Different types and/or levels of personal searches require greater or lesser degrees of justification and raise different constitutional considerations. The more intrusive the search, the greater the degree of justification and constitutional protection required.Footnote 25

A body search or "frisk" is a thorough search of a person's clothing at the time of an arrest.Footnote 26 During a body search, an RCMP member may ask a person to empty their pockets and subsequently proceed to "pat down" or "run" his/her hands along a person's outer clothing as a means of finding weapons or evidence.Footnote 27 Body searches incidental to arrest are conducted to ensure the safety of police and the public, to avoid the destruction of evidence, or to locate evidence connected to the offence for which the arrest was made.Footnote 28 A body search incidental to arrest may be conducted at the scene, prior to a subject being transported in a police vehicle, and may also take place prior to a subject being lodged in a cell. As such, a subject could undergo two body searches incidental to a lawful arrest (between the time of arrest and the subject's incarceration in cells).

The police authority to conduct a body search incidental to a lawful arrest does not require the existence of reasonable or probable grounds.Footnote 29 In Cloutier v Langlois, the Supreme Court of Canada held that "[t]he minimal intrusion involved in [a frisk] search is necessary to ensure that criminal justice is properly administered."Footnote 30 The authority to conduct a body search incidental to arrest is, however, discretionary—not a duty. In Cloutier, the Supreme Court held that:

The police have some discretion in conducting the search. Where they are satisfied that the law can be effectively and safely applied without a search, the police may see fit not to conduct a search. They must be in a position to assess the circumstances of each case so as to determine whether a search meets the underlying objectives.Footnote 31

In Cloutier,the Supreme Court established three principles regarding police authority to search incidental to arrest:

- a) the police have the authority to conduct a search—not a duty;

- b) the search must be for a valid objective in pursuit of the ends of criminal justice; and

- c) the search must not be conducted in an abusive manner.Footnote 32

Within these legal parameters, body searches incidental to arrest, such as frisk searches, are lawful and appropriate.Footnote 33

While body searches are a relatively routine policing practice upon arrest, strip searches are not. A strip search involves the removal of some or all of a person's clothing to allow a visual inspection of the person's private areas (i.e. the genitals, buttocks, breasts [in the case of a female]), or undergarments.Footnote 34 According to the Supreme Court of Canada, strip searches are inherently invasive and degrading and cannot be conducted as a matter of routine policy.Footnote 35

In R v Golden, the Supreme Court ruled that:

In light of the serious infringement of privacy and personal dignity that is an inevitable consequence of a strip search, such searches are only constitutionally valid at common law where they are conducted as an incident to a lawful arrest for the purpose of discovering weapons in the detainee's possession or evidence related to the reason for the arrest. In addition, the police must establish reasonable and probable grounds justifying the strip search in addition to reasonable and probable grounds justifying the arrest. Where these preconditions to conducting a strip search incident to arrest are met, it is also necessary that the strip search be conducted in a manner that does not infringe s. 8 of the Charter.Footnote 36

Common law rules require that when strip searches are carried out incidental to arrest, without prior judicial authorization (e.g. without a warrant), they should be conducted in a manner that interferes as little as possible with the privacy and dignity of the person being searched and that the proper balance is struck between the privacy interests of the person being searched and the interests of the police and the public to preserve relevant evidence and to ensure the safety of police officers, detained persons and the public.Footnote 37 In Golden,the Supreme Court set an important legal precedent for the police to decide when to conduct a strip search incidental to arrest to ensure compliance with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter).

The Supreme Court also states that a strip search involves "the removal or rearrangement of some or all of the clothing of a person so as to permit a visual inspection of a person's private areas, namely genitals, buttocks, breasts (in the case of a female), or undergarments [emphasis added],"Footnote 38 clearly taking the view that requiring a subject to strip down to their undergarments constitutes a strip search. The Provincial Court of British Columbia (Youth Division) reiterated this position and added that the definition of a strip search included removal of the brassiere.Footnote 39

Internal searches, also known as cavity searches, involve the physical inspection of body orifices. These searches are typically conducted by medical practitioners in a hospital setting. Internal searches are the most intrusive and are a much greater infringement on a person's integrity. As previously noted, common law rules stipulate that the more intrusive the search, the greater the degree of justification and constitutional protection required. Thus, a body search would require less justification than a strip search, which would require less justification than an internal search.Footnote 40

In a 2013 report, Human Rights Watch raised concerns about women and female youth being searched or strip-searched by male members of the RCMP. In particular, the Human Rights Watch report recommended that the RCMP "[e]liminate searches and monitoring of women and girls by male police officers in all but extraordinary circumstances and require documentation and supervisor and commander review of any such searches" and to prohibit strip searches by members of the opposite sex under any circumstances.Footnote 41 The report also refers to human rights standards that recommend that body searches by government authorities should only be conducted by persons of the same sex.Footnote 42

The RCMP confirmed to the Commission that the gender breakdown of its members in the North District is 80% male and 20% female. As a result, 32.5% of North District detachments are staffed by male members only (as of October 1, 2014).Footnote 43

RCMP Policy

RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual – Personal Search Policies

In relation to personal searches, RCMP policies address three types of search: body search (i.e. frisk search); strip search; and internal search (i.e. body cavity search).

For the purposes of this investigation, the Commission examined:

- National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 18.1. "Arrest and Detention," section 5., "Searches" (dated May 15, 2013);

- National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 19.3. "Guarding Prisoners and Personal Effects" (dated August 21, 2013);

- National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.1. "Authority to Search" (dated May 28, 2013); and

- National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search" (dated February 13, 2013).

RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search" specifically addresses personal searches. It defines and describes the types of personal searches: body search (i.e. frisk), strip search and internal search.

The national policy defines body search as "a thorough search of the clothing at the time of an arrest." It specifies that body searches "will be conducted in a manner that interferes as little as possible with the privacy and dignity of the person being searched and does not infringe on section 8, Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms."

The national policy defines a strip search as "a thorough search and examination of a person's clothing and visual inspection only of the body including the genital and anal areas, without physical contact." The policy also states that strip searches are not considered routine police practice, and provides direction on the legal requirements that must be met to conduct a strip search (i.e. "should only be conducted when there are reasonable grounds to believe the suspect is concealing evidence relating to a crime or items that may be used to cause injury, death or aid in escape").

In reviewing these policies, the Commission sought clarification from RCMP National Headquarters, the British Columbia RCMP Division and the RCMP Depot Division regarding the definitions of body and strip searches, and whether a search requiring a subject to strip down to his/her underwear would be considered a strip search or a body search. The RCMP National Headquarters and the RCMP in British Columbia both responded that in accordance with national policy, such a search would not amount to a strip search.Footnote 44 Depot Division, however, reported that from their perspective, requiring a subject to strip down to his/her undergarments was a strip search.Footnote 45

Based on the above responses, it appears that the national policy definitions for body searches and strip searches are insufficiently clear to guide members regarding whether a personal search is a body search or a strip search. This leads to concerns surrounding the consistent application and articulation of reasonable grounds to conduct a search.

Finding No. 1: The RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual definitions of "body search" and "strip search" are unclear and do not provide sufficient guidance for members to clearly differentiate between the two.

According to the Supreme Court, a strip search involves "the removal or rearrangement of some or all of the clothing of a person so as to permit a visual inspection of a person's private areas, namely genitals, buttocks, breasts (in the case of a female), or undergarments [emphasis added]."Footnote 46 Thus, it appears that the RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual definition of strip search is not consistent with this definition.

Finding No. 2: The definition of "strip search" provided by the RCMP's national policy is not consistent with the definitions provided by current jurisprudence.

Recommendation No. 1: That the RCMP update its National Headquarters Operational Manual policy definitions for "body search" and "strip search" to eliminate ambiguity and ensure that the definitions are consistent with current jurisprudence.

The national policy requires that a strip search must:

... be authorized by a supervisor when one is available; be conducted by a member of the same gender; be conducted quickly and where possible, in a manner so that the detainee is not completely undressed at any time; be conducted in a manner that is not abusive; and must not be conducted by more members than necessary, to ensure the safety of the members/detainee [emphasis added].Footnote 47

In this regard, during an interview with the Commission, RCMP members from National Headquarters, Contract and Aboriginal Policing Directorate, indicated that in most circumstances a supervisor is reachable, by telephone if not in person. They further noted that there should always be a watch commander or supervisor on-call, and in smaller detachments, if and when a supervisor is not available, a supervisor from a detachment close by may be relied upon. That being said, the RCMP confirmed that in exigent circumstances, a strip search could take place without obtaining a supervisor's approval.Footnote 48 Interviews with the British Columbia RCMP confirmed that this is the case in the Division.Footnote 49

While obtaining the approval of a supervisor prior to conducting a strip search is a good means of ensuring internal oversight, in the Commission's view the addition of the caveat "when one is available" significantly diminishes the stringency of this provision.

Finding No. 3: The RCMP's national policy requirement that members obtain the approval of a supervisor for a strip search "when one is available" is insufficiently stringent to ensure that such approval will be sought in all but exigent circumstances.

Requiring mandatory supervisory approval prior to conducting a strip search, unless exigent circumstances exist (e.g. an immediate strip search be conducted for the preservation of evidence and/or for the safety and security of members, the detained person and/or the public), would not appear to impose an undue burden on RCMP members.

Recommendation No. 2: That the RCMP amend chapter 21.2. of its national policy regarding personal searches to ensure more robust supervisory oversight by explicitly requiring a supervisor's approval prior to conducting a strip search unless exigent circumstances exist.

The national policy also stipulates that a member conducting a strip search "must be prepared to demonstrate [in writing] exactly how each criteria of R v Golden was met [emphasis added]."Footnote 50 This requirement is much less rigorous than requiring a member to document these articulations in a report or in a notebook. The RCMP acknowledged to the Commission that while unclear, the policy is meant to direct members to articulate in writing how the criteria for a strip search are met.Footnote 51

The national policy also includes a section on "Precautions," which provides additional guidance and direction to members, including section 4.3. stating: "Do not search a person of the opposite gender unless immediate risk of injury or escape exists" and section 4.4. reiterating that "[i]n accordance with sec 2.4., conduct a strip search only on a person of the same gender, and in private."

Based on the above, while sections 2.4. and 4.4. state that a strip search should "be conducted by a member of the same gender," it is unclear whether section 4.3. only applies to body searches (frisks) or whether a member can conduct a strip search on a person of the opposite sex if immediate risk of injury or escape exists.

Finding No. 4: Sections 4.3. and 4.4. of RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. lack clarity with respect to when strip searches by a member of the opposite sex are permitted.

In this regard, members of RCMP National Headquarters, Contract and Aboriginal Policing Directorate, and the British Columbia RCMP confirmed that a strip search of a subject of the opposite sex can take place in exigent circumstances.Footnote 52 It should also be noted that during interviews with the Commission's investigator, when asked about personal search policies and procedures, RCMP members from the British Columbia North District consistently responded that while opposite sex body searches are not uncommon, opposite-sex strip searches do not occur. Further, most of the members interviewed indicated that strip searches in general, including those of persons of the same sex, are extremely rare occurrences and/or do not occur. Members also stated that in the rare circumstances when strip searches of women occur, female guards and female RCMP members are generally available to conduct them.Footnote 53

Recommendation No. 3: That the RCMP amend chapter 21.2. of its national policy regarding personal searches to clarify if and when a strip search of a person of the opposite sex is ever permitted. Further, the policy should articulate the circumstances or criteria that must be met prior to conducting or overseeing a strip search of a person of the opposite sex (i.e. if immediate risk of injury or escape exists and/or in exigent circumstances).

Chapter 21.2. of the RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual also addresses internal searches. Section 3. of chapter 21.2. defines an internal search as a search of body orifices (excluding the mouth) and specifies that such searches are "highly intrusive and an assault on an individual's dignity" and are only to be conducted by a medical practitioner. While the policy provides general guidance, it does not inform members about the required approval process or reporting requirements. In light of the affront to personal dignity inherent in this type of search, the policy should clearly outline the necessary grounds required to conduct an internal search, the appropriate approvals that must be obtained, and the reporting requirements.

Finding No. 5: Section 3. of RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. does not provide clear direction to members on the required grounds to conduct an internal search, the necessary approvals or reporting requirements.

Recommendation No. 4: That the RCMP amend its internal search policy to ensure that it clearly specifies the necessary grounds required prior to conducting an internal search as well as the required approvals.

Section 5. of the RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. relates to a member's reporting requirements for personal searches. It requires that RCMP members retain "on file" their notebook entries in which they articulate the reasons for the search and the manner in which the search was conducted, whereas section 5.2. states: "If you are unable to articulate in your notes, the procedures as outlined in sec. 2.4., seek authorization from an available supervisor, whenever possible [emphasis added]."Footnote 54

Section 5.2. does not explain the circumstances under which a member would be considered "unable to articulate" the requirements under section 2.4. or what a supervisor would be asked to authorize under this provision. When asked about the policy, RCMP members in the National Contract and Aboriginal Policing Directorate were unable to explain the purpose and application of this section.Footnote 55

Given the intrusive and humiliating nature of strip searches as well as the potential Charter implications of an unreasonably conducted strip search, the national policy should be clarified and strengthened by requiring that members articulate, in writing, how each of the required criteria is met. The policy should equally set out where this information should be captured (i.e. on the prisoner report, the occurrence report, and/or in the member's notebook). Clarifying and strengthening reporting requirements will eliminate ambiguity, increase reporting transparency, enhance accountability, as well as provide a means to evaluate, measure and assess compliance with policies and procedures.

Finding No. 6: As written, section 5.2. of RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. is unclear and creates ambiguity regarding the section 2.4. requirement to articulate the reasons for and manner in which a search was conducted, and where this information should be recorded.

Recommendation No. 5: That the RCMP amend chapter 21.2. of its national policy regarding personal searches to ensure that the policy addresses the member's requirement to articulate the reasons and manner of the search in writing, including the information members are required to document and where it must be recorded.

In its review of RCMP policy documents, the Commission noted that the RCMP's national policy does not provide any guidance or direction to members in relation to searching a transgendered or inter-sexed person. While this specific area was not included in the scope of this investigation, the Commission is of the view that RCMP policies, procedures and training should include provisions to address searching a transgendered or inter-sexed person.

The Commission also noted that neither RCMP national policies and procedures on personal searches nor the policies governing the use and application of closed-circuit video equipment in cell block areasFootnote 56 provide guidelines or direction to members in relation to recording/capturing personal searches on cameras or any limitations or restrictions in this regard. This is particularly relevant in light of the recent case (R v Fine)Footnote 57wherein the British Columbia Provincial Court ruled that the Kelowna RCMP violated a woman's Charter right to be secure from an unreasonable search by videotaping and broadcasting the footage to a monitoring room while she was partially naked. Thus, the Commission believes that the RCMP should amend relevant policies and procedures to ensure that they address the use of closed-circuit video equipment during strip searches in order that the searched person's Charter rights are not infringed.

British Columbia RCMP Division Operational Manual – Personal Search Policies

British Columbia RCMP Operational Manual policies regarding personal searches are captured under British Columbia RCMP "E" Division Operational Manual chapter 21.2. (dated July 28, 2006). As previously noted, divisional policies are meant to supplement and expand on national policies and to provide additional division-specific guidance or provincial context.

Section 1. refers members to the national policy on personal searches; states that all prisoners must be searched by a member before being placed in cells; and indicates that prisoners may be searched by a member of opposite sex, if: another member or guard is present during the entire search; or in an emergency. This section also emphasizes that members must "evaluate the circumstances and exercise their judgment when conducting prisoner searches."Footnote 58 Section 1. of the British Columbia RCMP Operational Manual chapter 21.2. is generic and vague. The section does not differentiate between body and strip searches. As a result, in stating that searches may be conducted by members of the opposite sex if "another member or guard is present during the entire search; or, it is an emergency," the chapter fails to make clear whether this applies to body searches, strip searches, or both.

Section 4. of the policy states:

- If determined through a frisk search that a prisoner is wearing a bra and the criteria for conducting a strip search is not met, and if officer safety would not be compromised, then the member/matron should:

- 4. 1. 1. instruct the prisoner to remove the bra without removing any clothing and surrender the undergarment to the member/matron; or

- 4. 1. 2. in a private area, aid the prisoner in the removal of the bra;

- 4. 1. 3. thoroughly search the undergarment; and

- 4. 1. 4. if there are no articulable concerns, return the undergarment to the prisoner to put back on.

- 4. 2. The seizing of a prisoner's bra and/or underwear prior to lodging the prisoner in cells is only to be carried out if there are articulable concerns that:

- 4. 2. 1. the underwire may be used as a weapon or to aid in escape; or

- 4. 2. 2. the undergarment may be used to aid in suicide.Footnote 59

During interviews with the British Columbia RCMP officials, the Commission was advised that the removal of a woman's bra was done for safety reasons and that this is a routine practice with extremely intoxicated women. They also stated that removal of the bra is considered part of a thorough body search, not a strip search.Footnote 60

As previously stated, under current jurisprudence, the requirement for a prisoner to remove her bra falls within the definition of strip search. The Provincial Court of British Columbia (Youth Division) ruled that the RCMP requirement for a female prisoner to remove her brassiere pursuant to general policy constitutes a strip search.Footnote 61 In addition, in 2013 the Saskatchewan Provincial Court and the Ontario Superior Court of Justice found that demanding that female detainees remove their bras (even though done discreetly without exposing their breasts) constitutes a strip search under the Golden definition.Footnote 62 Other court judgments also recognize that this practice is intrusive and should not be carried out as a routine matter without consideration of the circumstances.Footnote 63

If a member has reasonable grounds to believe that a detained person's bra poses a risk to the safety and/or security of police members, the detained person and/or the public, the policies, procedures, approvals and reporting requirements attributed to strip searches should apply. There is no indication that the removal of a bra is necessary in all cases to ensure the safety of members, the detainee and other persons. The prescriptive nature of the policy may result in unnecessary and excessive searches of women, contrary to the criteria set forth in common law. Given the court decisions referenced above, the Commission believes that removing a prisoner's bra or enjoining a prisoner to remove a bra constitutes a strip search, which requires reasonable grounds and must be reflected in policy.

Finding No. 7: The British Columbia RCMP policy mandating the removal of bras is contrary to common law principles. Absent reasonable grounds to conduct a strip search, the removal of a prisoner's bra is unreasonable.

Section 5. is the final section of the divisional policy, which outlines the Commander's responsibility to ensure that members are aware of the contents of the policy.

Based on the above, the Commission is of the view that British Columbia RCMP policy with respect to personal searches requires clarification and should be revised to reflect current jurisprudence.

Recommendation No. 6: That the RCMP in British Columbia amend its policy regarding personal searches (Operational Manual chapter 21.2.) to reflect current jurisprudence.

RCMP Training

Cadet Training Program

The Commission reviewed all RCMP Cadet Training ProgramFootnote 64 modules that specifically pertain to personal searches, including:

- a) Applied Police Sciences – Module 6, session 7 (version 8, September 20, 2012)

- b) Applied Police Sciences – Module 6, session 9 (version 8, June 19, 2014)

- c) Applied Police Sciences – Module 6, session 10 (version 8, February 26, 2014)

- d) Welcome Package Police Defensive Tactics, Appendix 9 – Types of Searches DARCS and ALPS the 4 C's – (version 8, January 18, 2013)

- e) Police Defensive Tactics – Session 8 – DARCS Procedures Standing Subject Search (version 8, April 1, 2012)

- f) Police Defensive Tactics – Session 9

The RCMP Depot Division confirmed that while the above modules and sessions are specifically dedicated to personal searches, cadets are expected to apply the relevant knowledge and skills in all subsequent training and scenarios during the Cadet Training Program.Footnote 65

In the RCMP Cadet Training Program's Applied Police Sciences modules, among other key topics cadets learn about their authority to search an individual who is lawfully arrested; the rights and freedoms afforded under the Charter; relevant case law; the appropriate safeguards to take when searching and escorting a detained person to the detachment; and the types of personal searches and the associated procedures.Footnote 66

These modules and sessions also include information about the RCMP's national policy on personal searches, including specific training on searching a person of the opposite sex. The training stipulates that "[a] member shall not search a person of the opposite sex unless immediate risk of injury or escape exists." Cadets are taught that "[u]nless a person of the same gender is available in a reasonable amount of time, then the arresting member will conduct a body search. What a reasonable amount of time is must be left up to the individual member based on his/her assessment of risk [emphasis added]."Footnote 67

In this regard, the Commission was informed that during the session, the course facilitator emphasizes that member availability and time, and other factors such as the weather, environment and situational factors, all influence the risk assessment and decision making of the officer in determining whether to conduct a body search of a subject of the opposite sex. The training provided is intended to help cadets develop the required skills and competencies to assess the risk of a given situation and make decisions.Footnote 68

As part of the Applied Police Sciences modules, cadets participate in role-playing scenarios on escorting prisoners to the cell block, searching the cell and the prisoner, as well as completing the required paperwork (i.e. prisoner report). Cadets also discuss the reasons for the search and seizure of effects from prisoners, including items that have or may have religious meaning.Footnote 69

In the Cadet Training Program, Police Defensive Tactics Training, cadets also learn about the types of searches and receive detailed training on how to conduct body searches of a standing subject and a prone subject. Cadets are reminded of the specific national policies on personal searches (including the grounds required to conduct a strip search) and the care required when searching a subject to ensure a complete and thorough search.Footnote 70

During these sessions, cadets also learn about searching a person of the opposite sex. In this regard, cadets are taught that common law authority does not make a distinction between sexes and that members may search anyone subsequent to a lawful arrest. Cadets are instructed to ask for a same-sex RCMP member to conduct the search and that an opposite-sex search is permitted under policy, depending on the risk environment (i.e. if immediate risk of injury or escape exists).Footnote 71 Cadets also receive a demonstration of the different techniques used when a male or female RCMP member searches a female subject (i.e. instead of using a flat hand technique while searching the chest/breast area, members are taught to search the chest/breast area with the edge of their hand and whenever possible to ensure the palm of the hand is directed away from the breast). Cadets are subsequently required to practice arrest and searching techniques and procedures using role-play.Footnote 72

Cadets are also taught that a strip search may only be conducted if "there are reasonable and probable grounds to believe the suspect is concealing evidence relating to a crime or items that may be used to cause injury, death or aid in escape."Footnote 73 Cadets are instructed that a strip search is to be conducted by a member of the same sex, and that the following conditions must also be met prior to/during a strip search:

- Must be authorized by a supervisor if one is available.

- Be conducted quickly and, where possible, so that the detainee is not completely undressed at any time.

- Be conducted in a manner that is not abusive.

- Must not be conducted by more members than necessary, to ensure the safety of the members/detainee.

Based on a review of the course materials examined, training in relation to personal searches is consistent with the law as well as national policies and procedures. Furthermore, training specifically in relation to body searches is exhaustive and comprehensive. Cadets are provided detailed instruction and demonstrations as well as time to practice the required skills and competencies. Training includes an appropriate combination of reference material, presentations, practical exercises (including role-play and scenarios) and video instruction, and teaches relevant policies, case law and section 8 of the Charter in a manner that provides cadets with the necessary basis for conducting searches according to the law.

Training in relation to strip searches is provided from a theoretical perspective only. Cadets learn about the strip search policies and procedures in theory and through written assignments, but do not conduct strip searches in practice.

In this regard, Depot Division informed the Commission that the Cadet Training Program is designed for basic training. The emphasis is hence placed on body searches because cadets will perform this type of search within a very short time of entering the field and regularly over the course of their career. Strip searches are not routine police procedure and are performed rarely. As such, training scenarios during the Cadet Training Program do not involve strip searches or the requirement to articulate whether reasonable and probable grounds for a strip search exist.Footnote 74

Further, when asked about the RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual definition of strip search and whether requesting a person to strip down to his/her undergarments constitutes a strip search, Depot Division responded that in their view, it did. That said, Depot Division also informed the Commission that the partial removal of clothing is not addressed during cadet training. Based on the Commission's review, it appears that the identified policy ambiguities and weaknesses are leading to training gaps which must be addressed. The Commission believes that the Cadet Training Program should include specific guidance to cadets on the distinction between a body search and strip search, the legal authority to conduct those searches and the articulation of the reasonable grounds to conduct such a search. The training should also provide opportunities for cadets to exercise discretion in determining whether to conduct a strip search.

Finding No. 8: By limiting training on strip searches to a review of relevant policies, procedures, law and written assignments, the RCMP Cadet Training Program fails to provide adequate training to cadets on what constitutes a strip search.

Recommendation No. 7: That the RCMP enhance basic training at Depot Division to ensure that cadets are cognizant of the legal requirements, and relevant policies and procedures for all types of personal searches.

British Columbia RCMP Division Training – Field Coaching Program and Pacific Region Training Centre

During the Field Coaching Program, coach officers provide basic "on the job training." In addition to the experiences gained through direct operational activities, new members are also required to complete assignments and tests. For the RCMP in British Columbia, this includes a specific module intended to familiarize new members with national, division and detachment policies. The module includes a review of search and seizure laws, statutes and RCMP policies.Footnote 75

Other than the training received during the Field Coaching Program, members do not receive any specific or dedicated training in relation to personal searches on a mandatory or ongoing basis. The Commission was informed, however, that all RCMP regular members must attend a mandatory Operational Skills Maintenance Re-Certification once every three years at the Pacific Region Training Centre.Footnote 76 According to the information provided by the Pacific Region Training Centre, this recertification includes a session on Scenario Based Training and Articulation. While personal searches are not part of the scenario-based training requirements, members are monitored during the scenario for communication with the dispatcher to see whether members request the presence of a member of the same sex to conduct a body search, if it is appropriate to their scenario.Footnote 77

The Pacific Region Training Centre informed the Commission that while the Operational Skills Maintenance Re-Certification does not specifically address personal searches, if during this recertification a member seeks clarification or asks a question, trainers use the Police Defensive Tactics training materials from Depot Division as the guide to answer any questions.Footnote 78 The Training Centre also reported that in addition to the mandatory Operational Skills Maintenance Re-Certification, members may, at the request of a member or detachment, receive refresher training on conducting personal searches at the detachment with the assistance of a Public and Police Safety Instructor, based on the needs and skills of the members and availability of a local instructor.Footnote 79

The Commission finds that the RCMP in British Columbia does not have dedicated, mandatory or ongoing practical training in relation to personal searches. When training is provided, at the request of a member or detachment, it is reportedly based on and consistent with RCMP national policies, Depot Division training, and relevant case law.

While it may not be practical or reasonable to expect members to conduct actual strip searches on persons for training purposes, the RCMP should consider whether to develop specific practical training on what entails a strip search, when it is appropriate and how to conduct a strip search for the Cadet Training Program or for subsequent training at the divisional level. Limiting strip search training to "on-the-job" learning exposes the RCMP to a higher degree of risk and error. This was clearly evidenced during the Commission's review when multiple members were unsure whether a strip search included stripping a person down to his/her undergarments. This may present an even greater risk for members transferred to remote locations, faced with the necessity or requirement to conduct a strip search without the benefit of formal training or practical experience, or access to more experienced personnel to provide guidance.

Furthermore, while internal searches likely occur rarely, members should learn the grounds required to conduct such a search, as well as how to ensure that the search is conducted appropriately and in accordance with the law. Members should know and learn about the required approvals and reporting requirements.

Finding No. 9: Relying on member or detachment initiative to request training, rather than mandating ongoing practical training in body searches or any training in strip searches in the Division, fails to ensure that members have adequate knowledge and experience in these areas.

Recommendation No. 8: That the RCMP enhance training in personal searches to ensure that Division members are cognizant of the legal requirements and relevant policies and procedures for body, strip and internal searches, and that such training also be included in the Operational Skills Maintenance Re-Certification.

Accountability, Compliance and Transparency

The Commission initially intended to conduct a file review to examine member compliance with RCMP personal search policies and procedures. As previously noted, the Commission was informed that the British Columbia RCMP's current records management system (Police Records Management Environment for British Columbia, known as PRIME-BC) does not track or otherwise account for the frequency and/or types of searches conducted; the approvals sought; the results of the search; or whether a search was conducted by a member of the opposite sex.

Interviews with members of the British Columbia North District consistently reported that strip searches are rare occurrences and that strip searches by members of the opposite sex do not occur. But the lack of appropriate tracking systems means that the RCMP is unable to fully account for the actions taken by its members in this regard and the Commission is unable to verify RCMP assertions regarding strip searches. Moreover, the lack of clear differentiation in RCMP policy between body and strip searches, noted previously, may mean that strip searches are being misidentified as body searches and are not being recorded appropriately. While members are expected to record this information in their notebooks, without formal records or appropriate means of tracking strip searches and their results, the Commission was severely limited in its ability to evaluate member compliance with policies and procedures or to determine if a systemic issue may exist.

RCMP detachments in British Columbia are required to conduct unit-level quality assurance reviews and are subject to management reviews, which include reviews of search and seizure practices. The search and seizure reviews are intended to determine whether proper documentation was completed, whether the search and seizure of items was compliant with legal requirements and directives, and whether the search and seizure of items was deemed reasonable within these authorities. The reviews are also meant to assist in determining whether the searches and seizures were conducted only when clearly authorized by law or with expressed consent.Footnote 80 During such a review, a sample of files is examined to determine whether search and seizure policies and procedures are being followed in practice. The fact that search and seizure is included in these reviews suggests that the RCMP regards this as a high-risk area needing regular review. But the review focuses largely on material search and seizure, rather than personal searches. As well, in relation to strip searches, while the Search and Seizure Guide links back to the requirements set out in RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. (specifically in relation to sections 2.4. and 2.5. as well as 5.1. in relation to a member's reporting requirements), it is unclear how a sample of files involving strip searches can be derived since information about strip searches is captured only in a member's notebook and is not otherwise tracked in existing records systems.

In this regard, the Commission obtained the Management Review reports conducted by the RCMP in British Columbia for detachments in the North District between 2008 and 2012. Of the 20 Management Review reports examined, four included sections addressing personal searches. Of these four reviews, one report revealed that the majority of members at a detachment did not possess the appropriate knowledge to justify their grounds for warrantless searches. The report found that while the file review did not identify any strip searches, further to interviews with detachment members, it was learned that all individuals being arrested for drugs seizures are being subjected to strip searches. In this regard, the review revealed that members are not adequately documenting the events/circumstances that occur during their investigations. The review recommended that the Unit Commander ensure that all members receive appropriate training in relation to legal authorities and policy requirements surrounding warrantless searches and strip searches as well as the need to properly document and justify their actions. Two reports found that members are not always clearly or consistently documenting the fact that a search was conducted incidental to arrest.Footnote 81

In Golden, the Supreme Court of Canada highlighted the importance to the police of keeping proper records of the reasons for and manner in which a strip search was carried out. In R v Muller, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice stated:

There must be a means by which authorities can account for and be held accountable for such procedures. The failure to record these events creates any number of problems. It is impossible to gauge how often these searches are conducted and the proportion that result in no evidence being found. The ability to examine and revisit practices is limited. Important evidence capable of disclosing systemic problems is effectively erased. There is no record kept for other purposes, such as a police complaint or civil action. Persons such as the accused in this case may be deprived of evidence relevant to the advancement of their constitutional rights. More generally, the absence of a record might carry an implicit or subtle message of impunity for police engaged in these searches, the notion being that, if there is no record, there will be no review. This is a dangerous prospect and one which the Charter cannot countenance. No state power should be left unchecked, particularly one involving invasive search of the person.Footnote 82

While the case above relates specifically to notebook entries (or more specifically the absence of notebook entries), and the guidelines in relation to "proper records" stipulated in Golden are not legislated, it seems reasonable nonetheless to expect the police to maintain an official record of police actions and conduct when subjecting a person to a strip search without a warrant.

In the United Kingdom, the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 codes of practice establish a framework of police powers and safeguards in relation to core policing activities (i.e. specifically relating to stop and search; arrest; detention; investigation; identification; and interviewing detainees). In this regard, the Police and Criminal Evidence Act Code C provides clear and specific guidelines in relation to the detention, treatment and questioning of persons by the police. Annex A of this code outlines specific requirements for when and how a strip search should be conducted, including the requirement that certain information be captured on the custody record, namely the reason it was necessary, those present and the results of the strip search.Footnote 83

The specific requirement to record the details of the search on the custody record is a paramount feature of these guidelines that not only increases police accountability and transparency but also ensures that compliance with policies and procedures can be measured.

Furthermore, while tracking personal searches may not be a "standard practice" for all police services, it is not without precedent in Canada. The Toronto Police Services Board requires the Chief of Police to report annually to the Board on the number (frequency) of strip searches; the reasons articulated for the searches; and the results of both strip searches and internal searches (i.e. cavity/orifice searches).Footnote 84 This information is made public on the Toronto Police Services Board's website. In this regard, in 2013 the Toronto Police Service reported conducting 20,152 strip searches, representing 34% of all arrests made. The report further indicates that the police found evidence such as drugs in just over 1% of these searches.Footnote 85

Other Canadian police services also collect data and statistics on the frequency, details and results of strip searches. The Commission contacted 35 Canadian police services to ask about personal search policies and procedures. Of the 18 that responded, four reported collecting and being able to derive statistical data in relation to strip searches (this includes information such as the frequency of strip searches; the person's age, sex and ethnicity; as well as the results of the search).Footnote 86

The Commission also obtained the search policies and procedures of a municipal police service in British Columbia. These include very specific directions and procedures on when and how to conduct a strip search and the required authorization, as well as detailed instructions on what information must be recorded and where the information must be captured. The police service also requires its officers to record the required information on a specific strip search template and the arrest report, which are both electronic forms on PRIME-BC. This records management system is also used by the RCMP in British Columbia, as previously noted.

The Saskatchewan RCMP divisional policy on personal searches sets out strip search procedures that must be followed if a strip search is conducted, including the requirement to document the following on the operational file:

- Date, place of arrest and time.

- Name and sex of detainee.

- Authority to Arrest.

- Place of strip search and time.

- Name of officer(s) conducting search and names of other officers present at time of arrest through to search.

- Reasonable grounds for strip search. What were the facts that enabled you to draw the conclusion that there was concern for:

- safety of officer, detainee and other persons; and

- purpose of discovering evidence related to the reason for arrest to preserve it and prevent destruction.

- Notification and consent from supervisor. In exigent circumstances this may not be possible, and if that is the case it should be noted.

- Offer the detainee an opportunity to produce the material being sought.

- Was advice or assistance from a trained medical officer considered and documented on the operational file?

- Manner of strip search: How was it conducted at the scene in exigent circumstances. Indicate steps that were taken to enable the search to be done to the extent possible under the circumstances in a dignified way out of public view.

- Manner of strip search at detachment. Indicate place and circumstances to show dignified and private search.

- Was the search conducted by a person of the same sex as the detainee?Footnote 87

The Commission believes that the Saskatchewan RCMP procedures for strip searches set a high standard, consistent with that of some other Canadian police forces, which could serve as a model for the RCMP in British Columbia. That said, while the procedures require members to capture the details and manner of the search on the operational file, the RCMP Division in Saskatchewan does not currently have the means to collect data or derive statistics on strip searches.

In addition to providing accountability for the use of a highly invasive procedure, systematic recording and reporting on strip searches increases transparency and thus contributes to public trust in the police.

Finding No. 10: From an accountability perspective, the Commission finds that the RCMP's National Headquarters and British Columbia divisional personal search policies and practices are not adequate.

Recommendation No. 9: That the RCMP amend its National Headquarters and British Columbia divisional Operational Manual personal search policies to enhance transparency and accountability by ensuring the policies include an appropriate means of recording, tracking, and assessing compliance, thus facilitating independent review.

Women and Youth

The Commission reviewed the RCMP's personal search policies and training in terms of their specific application towards and implications for police interactions with woman and youth. Human Rights Watch recommended that the RCMP "eliminate searches and monitoring of women and girls by male police officers in all but extraordinary circumstances and require documentation and supervisor and commander review of any such searches" and to prohibit opposite-sex strip searches under any circumstances.Footnote 87

As previously mentioned, body searches are a relatively routine police practice, conducted to ensure the safety of RCMP members, the detainee and the public; and to avoid the destruction of evidence or to locate evidence connected to the offence for which the arrest was made.Footnote 89 As such, the courts have made a clear distinction between "body searches" and "strip searches."